Smilin’ Jack and the “Twin Engine Queenie”

After World War One, the American and Canadian public became preoccupied with the true adventures and exploits of aviator pilot heroes. Every week would bring another speed record, new aircraft endurance records, and even sudden death. This soon inspired a series of new aviation adventure strips in American newspapers.

Tailspin Tommy by Hal Forrest appeared in 1929, then Scorchy Smith by John Terry in 1930, followed by an aviation pilot who would last for the next forty-years, “Smilin” Jack” by Zack Mosley, appearing 1 October 1933. This first Sunday strip appeared in the Chicago Tribune with the original title “ON THE WING” featuring a young kid pilot named “Mack” Martin. The amusing part is the fact artist Zack Mosley first created a pilot hero who never smiled and always carried a grim face.

This is the original Sunday newspaper strip, which contained excellent airplane art, but lacked a good story line. The young pilot named Mack Martin had an on-off airport romance with a girl, always involving another pilot, which proved to be very dull, and undramatic.

The good point was Mosley also created a closing two or three panel strip called “Air Facts” based on real functions of the airplane. Please keep in mind that his young American male readers of Air Facts were in the 10-15 age group and they would be going to war in eight years. The Canadian male readers would be going to war in just six years.

Captain Joseph Patterson was the publisher of the New York Daily and co-owner of the Chicago Tribune in the 1930s. In 1933, he looked over hundreds of comic strip submissions from cartoonists and picked Zack Mosley as a new strip he wanted to publish in the New York Daily News and Tribune comic sections. During the first interview between publisher and artist both men recognized they had taken flying lessons as student pilots at Chicago National Airport and a friendship was formed. In the next three months, artist Zack Mosley became known as “Smiling” Zack” due to his jolly attitude and ever-ready smile.

As a pilot, publisher Patterson realized that something was needed to give more spark and adventure to the comic strip and that included a change in title as well as a happier pilot character. The grim faced Mack appeared in the very last issue of “On the Wing” [frowning] 24 December 1933, and was replaced by a new strip called “Smilin’ Jack.” Artist Zack Mosley was in fact ordered by publisher Patterson to change the name, which he had earned from the Patterson office staff and just change “Zack” to Jack and history was made. Sometimes fact is much stranger that fiction, and with the very first issue of the new strip “Smilin Jack” on 31 December 1933, the new pilot smiles in every panel. The strip continued to evolve and by 1935 became a seven-day-a-week continuing narrative, capturing a huge mature reading base, including future WWII pilots. From 1936 to 1948, the series became the greatest aviation comic strip of all time, with hero pilot Smilin” Jack flying every aircraft from that period. Mosley developed a semi-humorous character base with one after another pretty lady, romance, heartbreak, fights, stunt flying, and many airplane crashes. The main female character became another blonde, Air Hostess Dixie Lee.

The first issue newspaper strip published on 31 December 1933.

January 1934 newspaper strip and the development of main characters, Rufus and Dixie Lee.

The original strip of 1933, featured a young blonde lady named Mickey, and Zack Mosley continued with a main female character introducing a Blonde air hostess named Dixie Lee, in January 1934. Dixie remained in the strip and became the main ‘squeeze’ of hero pilot Smilin’ Jack, however much like some real pilots, Jack had a large number of other lady friends and romantic adventures. Dixie Lee was probably the first fictional comic strip member of the ‘mile-high-club.’

Smilin’ Jack always enjoyed the company of many lovely ladies, who were drawn with the same technical details and accuracy as the aircraft he flew. They were known as “De-Icers” [melt ice off a wing] and each had a name, Gale on left in red dress and Miss Joy on right in blue dress. Other interesting characters joined Jack in his adventures, seen in background is Jack’s Polynesian friend called “Fat Stuff.” This fat pal was always popping buttons which were swallowed by a chicken, that followed him around the airfield. Blonde haired pilot friend “Downward Jaxon” was so handsome all the girls fell in love with him, and for that reason his face was never shown in a cartoon strip.

Zack Mosley was an experienced pilot and some strips contain his 1936 licence number. Jack’s fast-paced, action-packed adventures appeared in Popular Comics [A Dell Magazine Publication] as a color reprint beginning in early 1939.

In 1942, each comic book cover featured Smilin’ Jack with a serious face as he took on a new enemy the Japanese. The series of “De-Icer” girls appeared as nose art on a number of World War Two aircraft, painted by a nose artist, however Zack Mosley never drew any cartoon girls in sexy, nude, or bad taste. That’s what historians of the comic strip and comic book world reported, but I always wondered if he possibly created any original nose art girls for the war effort. The answer to that question came with research on the 319th Bomb Group [Medium] B-26B Marauder Bomber Group, which I was conducting from 1981 to 1995.

Zack Mosley liked to hide small detail in his comic strip, and this ‘flying’ pin-up of Dixie Lee appeared as aircraft comic ‘nose art.” I wondered if she ever appeared as nude nose art in WWII on any combat aircraft?

The 319th Bomb Group [Medium] was constituted on 19 June 1942, at Barksdale Field, Shreveport, Louisiana, and activated seven days later [Order #143]. They had 43 Officers and 9 enlisted men on strength. On 27 June, 410 enlisted men from the 17th B. G. were transferred to the 319th, for training. No known Bomb Group badge was created during WWII, however each squadron designed an ‘unofficial’ squadron badge seen above. [Left top] 437th B. Squadron, [top right] 438th B. Squadron, [bottom left] 439th B. Squadron, [bottom right] 440th B. Squadron. They trained in the new Glenn Martin B-26B Marauder at Barksdale Field, Louisiana, 26 June to 6 August 42 [first phase shortened to four weeks] then Harding Field, Louisiana, 6 to 27 August 1942. This revolutionary new twin-engine Marauder was a most advanced combat-ready powerful medium bomber aircraft, with the first training flight on 3 July 42. They had 31 [B-26A] classified as AT-23 aircraft for training, [serial numbers 41-17345 to 41-17476] first crash on 16 July, pilot 1st Lt. Lipscomb, killing M/Sgt. Courtney. Three more would follow, [Phase two] 23 August 42, pilot 2nd Lt. Richard Farnsworth crashed killing all his crew, he survived with serious injuries. Two more crews would be killed during training, totalling eighteen.

This is a production B-26F-2 model which has been stripped [no guns] and was used for training of Marauder crews in the United States, given designation AT-23A later [TB-26G]. This was the type of bomber the young 319th aircrews trained in during their first phase of Operational Training at Louisiana. They were given just nine weeks to be flight ready, their combat operational training would be completed in England under the 8th Air Force. That became a problem for some young crews who needed more experience.

After the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States entered WWII [declared war] on 8 December 1941. American and British leaders now set a date for a meeting to form overall plans for a total American-British global war. This special meeting took place at Washington, D.C. from 24 December 1941 until 14 January 1942, and was named the Arcadia Conference. Four major decisions were reached during the conference, the combined plans of a British-American war effort, the war against Germany, the decision to stop the Japanese attacks in the Pacific, and fourth being the invasion of French North Africa, called operation TORCH. The air support for TORCH would fall under two commands, the Eastern Air Command under the British and the Western Air Command under the American 12th Air Force. The American air forces were still in the building stage and air units of the new Twelfth would draw heavily from the growing resources of the 8th Air Force in England. Fourteen units from the 8th Air Force were now transferred to the Twelfth Air Force and eight additional new units were assigned directly from the United States. The United States Army Air Force now decided to move the new units from the U.S. [Presque Isle, Maine, USA] to Goose Bay, Labrador, [British colony] to Narsarsuaq Fjord, Blue West 1, [Denmark] and Reykjavi, [Iceland] to Scotland and Shipdham, England. The training of these new units would be completed by the 8th Air Force in England, and then they would move directly to the 12th Air Force in North Africa.

The first 54 B-25Cs of the 310th Bomb Group left Presque Isle, Maine, on 24 September 1942, but due to increasingly bad winter weather conditions, the last aircraft did not arrive in England until early December. The 47th Bomb Group followed with 58 A-20Bs with one crew lost [Atlantic] and six aircraft abandoned in Greenland, due to severe winter weather conditions. The 319th bomb Group would now follow with 57 new B-26B bombers, the first Martin Marauder to arrive in England. Before the 319th could finish their first stage training, [1 August 1942, at Barksdale Field] they were ordered to move and begin phase two training at once. After just four weeks training they moved to 2nd phase training at Harding Field. Upon graduation from training at Harding Field, 27 August 42, the first pilots had received only 90-100 hours in the Marauder, and only ten hours of instruction on how the aircraft operated. Some co-pilots had only received 50-70 hours flying time in the new Marauder and much less on the instruction of the aircraft performance. Four fatal crashes occurred during the last phase of training, possibly to lack of proper crew training. Now, due to a shortage of Martin B-26B Marauder bombers from the Omaha factory, the 319th departure move was delayed. In a rush to speed up their departure the 319th were issued with 57 new Marauders, 14 which that had been checked-out by the 320th Bomb Group. The 320th Flight Echelon was at Baer Field, Fort Wayne, Indiana, where a very talented nose artist in the 320th B.G., 441st Bomb Squadron, Sgt. George Ruesch was completing nose art images on most of these 14 new Marauder bomber aircraft. Many of the bombers had the same nose art on each side of their nose area. Superstition had it that it was bad luck to change the original nose art name or image, so most of the 319th bombers flew with the original nose art created by Sgt. Ruesch. [There was also no time to repaint any of the original nose art] At this early point in the war the naming of Marauders was a popular event for the ground crews, who were the only ones who could really call the aircraft ‘their’ own.

The Crew Chief and his ground crew members were in fact assigned to one aircraft, while the pilot and his aircrew were assigned to whatever B-26 that was picked for them to fly. It is impossible to trace any American artist who repainted new nose art on these early 319th B. G. Bombers, so I am just crediting all nose art to Sgt. Ruesch. The official ‘unclassified’ records of the 319th B. G. state the following – “Baer Field, Fort Wayne, Indiana, 21 September 1942, was a mixture of inefficiency and nonsense at its very best. Standard procedure on arrival at Baer Field was to turn all aircraft over to the Depot for an acceptance check and modification, then re-issue to squadrons. The Depot neither had the brains or men to work on the new Marauder aircraft.” [That’s what it says] To get the work completed on time, the flight engineers, and ground maintenance men of the 319th took charge, and working around the clock managed to get the bombers of three squadrons on their way to Presque Isle, Maine. The 437th, 438th and 439th left at three day intervals for Westover Field, Maine, which was an intermediate stop reroute to Presque Isle, Maine. Then problems arrived with a new Depot Commander posted to Baer Field, along with a new Post Commander, and the rules changed. The new officers ordered all aircraft must follow the old regular routine regardless of the time it took. The poor old 440th Bomb Squadron had to sit and wait for the release of their new Marauder bombers by the Concentrated Command orders. The last Marauder in the 440 B.S. departed for Westover Field on 18 October 1942, and they were now three weeks behind the first three squadrons of the 319th Group. This would possibly later cost the lives of three complete 440th Marauder aircrews.

Ten Marauders in the 440th B. Squadron left Presque Isle, Maine, on 13 October 1942, but most of the 20 Marauder aircraft in the 440th B.S. would never reach England, they only made it to Southwestern Greenland, and the base code named Bluie West 1, Greenland.

Micro-film copies from the 319th Diary on the 440th B. Squadron move to Goose Bay, Labrador and then to Narsarsuaq Fjord, [61.10’ North 45.25’ West] code named Bluie-West One, Greenland.

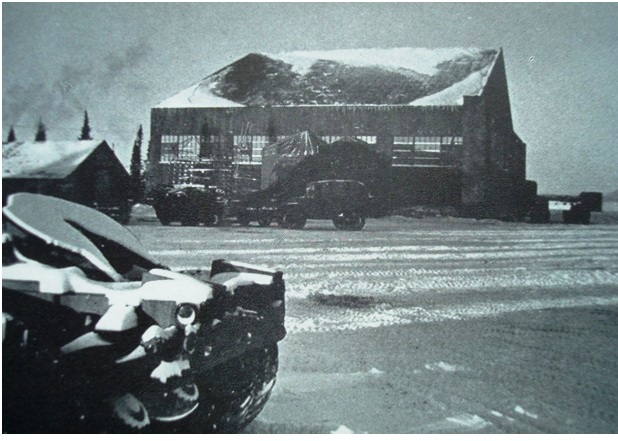

In October 1942, an American author named Ivan Dmitri was in Goose Bay, Labrador, working on his new book which would record the operations of the United States Air Transport Command. Newfoundland and Labrador did not become a Canadian Province until 1949, and during the war they were a self-governing colony of Great Britain. The British government had signed a 99-year lease with the United States for an American base at Goose Bay, Labrador, in exchange for old American destroyers for the British Navy. Canada was also required to sign a lease to construct an RCAF airfield at Goose Bay, located across the airfield from the American side. As the first three squadrons of the 319th Bomb Group arrived at Goose Bay, this American author captured some of the Marauder aircraft for publication in his book “Flight to Everywhere.” He also captured the American and Canadian workers who were still constructing this far northern American airbase, along with the many obstacles they had to overcome in minus -30 F temperatures. The images are not dated, but they were taken in the months of October and November 1942, and show the conditions which the last squadron [440th] of the 319th were trapped in for those same two months. [more on that later]

This was the one and only American aircraft hangar at Goose Bay in September 1942. Only two aircraft could be placed in this hangar for repairs. The other aircraft were repaired in the outdoors, heated by a Herman Nelson self-powered heating unit. This special heating plant was mounted on wheels and weighed only 290 lbs. It had a combination of collapsible canvas water-proof air hose ducts which came in three lengths, 14 foot, 24 foot, and 38 foot.

Historians at times get too caught up in the obvious and forget the small more important creations. [Can’t see the forest for the trees] This special preheating unit has been forgotten in time, but tens of thousands were manufactured at the Herman Nelson Corporation plant in Moline, Illinois, and they kept the WWII aircraft operating in Canada, Iceland, Greenland, and Goose Bay, Labrador. In the old bush pilot days, a pilot landed, drained the oil from his aircraft engine, then heated it the next day and poured the hot oil back into the aircraft engine, hoping it would start. In 1942, Goose Bay serviced 20 to 50 aircraft in a 24-hour period, only thanks to the American Herman Nelson aircraft heater.

One 319th B. G. Marauder is having an engine change, outdoors, where it’s -20 to -30 F. The aircraft is warmed by a Herman Nelson portable heater which blows hot air into the aircraft by the two hoses entering the landing gear area. Outdoor repairs would be impossible without these special heaters. The special designed tent covers the engine and wing area, trapping the hot air, while the ground crew complete repairs.

This is a 319th B.G, Marauder, serial 41-17830, 439th B. Squadron and the valiant ground crews preparing to heat the aircraft engines for starting, pushing special built Herman Nelson heaters. This Marauder made it to England, [14th October] then North Africa, 21 November] and flew her first mission on 12 February 1943, Lt. Norred, was shot down 12 December 1943.

Hundreds of aircraft were arriving and departing Goose Bay at all hours and the runways must be kept clear. In the fall of 1942, one-hundred aircraft arrived and departed in a 24-hour period, and 21 of those hours were total darkness.

The American hospital at Goose Bay, Labrador, was still under construction.

But the American Officers Mess was open for business.

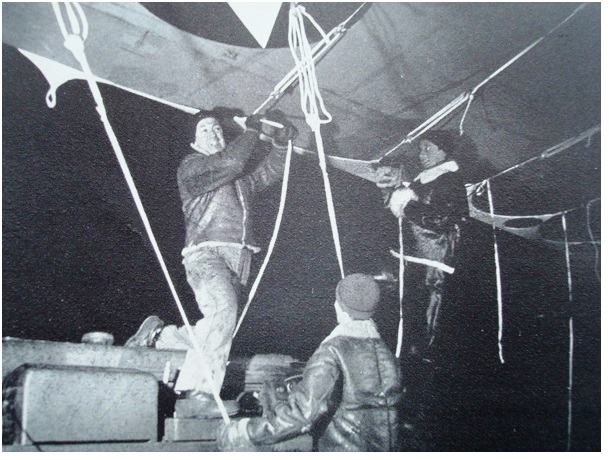

All bombers left the United States with a set of tarpaulins for covering the wings and gun positions. Each night is growing longer, and now they only have four hours of daylight to work in and by mid-November it will be darkness for 21 hours. This shows two B-25C bombers from the 310th B. Group which left Presque Isle, Maine, on 24 September 1942, but due to poor weather they would not arrive in England until the 6th of December.

Covering the main wing of a 319th Marauder in total darkness, possibly November.

The 319th Marauder Aircraft and first Nose Art

This is the original copy of the 319th B.G. Diary taken from micro-film and not the best to read. It records the end of training 27 September 42, and the assignment of new combat Marauder aircraft at Baer Field, Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Between the 12th and 27th of September 1942, the 319th B.G. were assigned 57 new Marauder B-26B medium bomber aircraft which were flown to Baer Field, Fort Wayne, Indiana. In total 43 were new Marauder bombers from the Omaha plant, ten delivered by 319 pilots and thirty-three by ferry pilots. Fourteen more new Marauders, which had been assigned to the 320th B.G. and flight checked by them, were now transferred to the 391th B.G., and many of these aircraft contained 320th nose art painted by Sgt. George Ruesch [below] from the 441st Bomb Squadron.

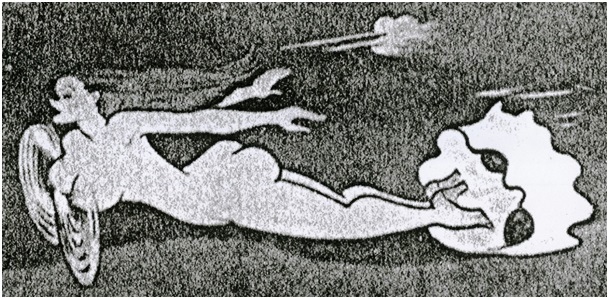

Sgt. Ruesh painted this “De-Icer” in full color from the comic strip Smilin’ Jack, but her serial number is not known. [41-7758, 41-7761, 41-17807, or 41-17827] She flew with the 440th B.S. and it is believed she was lost between Goose Bay, Labrador and Greenland. This author drawing is not to scale, but more scale images will follow.

I will now show a few nose art samples, and it is clearly evident from the style, the same artist [Ruesch] painted all the 319th transferred Marauder bomber nose art. I also believe the original artist intended to complete his lady nose art in full color, then his canvas was transferred to the 319th B.G. which was off to Goose Bay, Labrador. Few of his nose art creations survived the northern ferry route crossing in October, November, and December 1942.

B-26B Marauder, serial 41-17786, pilot Bob Krone, 438th Bomb Squadron. Flew no combat with 319th B.G., spun down in Greenland, twisting tail, then a crash landing at BW-1, 6 October 1942.

B-26B, Marauder, serial 41-17760, Pilot Danison 439th B. Squadron. 12 November 1942, thirty-six Marauder aircraft in the 319th [437th, 438th and 439th B. Squadrons] have arrived in England, nine are damaged beyond repair, and eight others required repairs. The Homesick Angel was one of these damaged bombers. Only fifteen 319th aircraft will leave for North Africa, and two will be shot down in France.

B-26B, serial 41-17753, Pilot Marshall, 439th Bomb Squadron. Completed the ferry route to England, then flew to North Africa. Transferred to 17th B. Group, 22 February 1943.

B-26B, serial unknown, “Twin Engine Queenie” original photo from Bernard Allen, possibly the original pilot. This red headed nude was painted by Sgt. Ruesch of the 320th B. Group, in color, and came from the Zack Mosley comic strip “Smilin’ Jack.” Photo from 319th B.G. Historian collection Esther M. Oyster, 21 October 1993.

This photo was taken at Baer Field, Fort Wayne, around 15 September 1942, donated by Edward Kantarski, who I believe is one of the ground crew in the image. Obtained from Esther M. Oyster in October 1993. This is the only image to record the nose art name – “Twin Engine Queenie” which appears to be painted in orange or off-white lettering. The new Marauder B-26 was sleek, with short wings, and powered by two big Pratt & Whitney R-2800-43 radial engines. It was too ‘hot’ to handle for many young pilots, and as a result there were many accidents during training, including some fatal. In early 1942, the Marauder had earned the name “Flying Prostitute” as it had no means of support, and I believe this idea was all contained in the creation of the nose art painting by Sgt. Ruesch of the 320th B. Group.

This new B-26B Marauder serial 41-17838, was flown from Martin’s Omaha factory to Baer Field, Fort Wayne, Indiana, then delivered to the 320th Bomb Group Flight Echelon. The official 320th history records nose artist Sgt. Ruesch was at Baer Field completing plane names on the new Marauders. This image confirms the records as Sgt. Ruesch has painted a little Cupid with wings firing a bomb at the German enemy, with name “Mit Liebst, [With Love]. The Marauder is then transferred to the 319th B. Group, 440th B. Squadron, and the ferry crew of pilot Lorenzo D. Murray arrive to take over their new bomber, complete with nose art. The crew photo was taken in mid-September 1942. They will fly 41-17838 to Goose Bay, Labrador, Greenland, and combat in North Africa. Crashed 16 May 1943 at Rabat, North Africa.

“Show Me” flew with 440th B. Squadron, a Lady holding a bomb.

Lovely Louise flew with 439th B. Squadron, pilot Lt. Erwin.

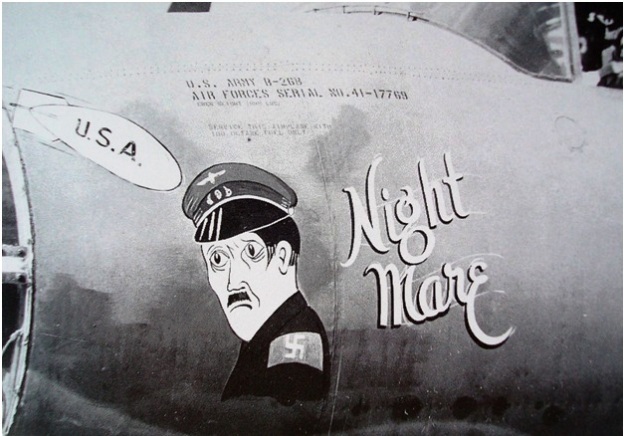

“Night Mare” serial 41-17769 was piloted by Lt. Forbes of the 437th Bomb Squadron. It was damaged and abandoned at Greenland in October 1942. History unknown, possibly the nine that arrived in England, and were used for spare parts.

Another crew photo taken at Baer Field, Fort Wayne, Indiana, late September 1942, Robert S. Young. The pilot was Lt. Brent and co-pilot Stewart. Assigned to the 440th B. Squadron, serial 41-17761 had a gold colored Boomerang.

This was a B-26B-2 Martin Marauder assigned to the 319th Bomb Group, 440th Bomb Squadron, serial 41-17862, assigned to pilot 1st Lt. Grover C. Hodge Jr. and crew in late September 1942.

The little rifle tooting soldier [Snuffy Smith] was a most famous cartoon character from 1942, and came from the cartoon strip called Barney Google and Snuffy Smith. The original American comic strip first appeared on 17 June 1919, titled – “Take Barney Google, F’rinstance.”

Created by cartoonist Billy DeBeck, it featured Barney Google, a born loser, who had a great difficulty in adjusting to main-stream life. Barney was short, smoked cigars, had a potato-shaped nose, a wisp of a mustache and huge saucer shaped eyes. His eyes became a hit song “Barney Google with the Goo-Goo-Googly Eyes.” Almost all of the characters were exaggerated hillbillies, with sharp-tonged gossipy women. The strip had a wide range of hillbilly humor and slang, which became a large part of American WWII aircraft nose art.

The names “heebie-jeebies, shiftless skonk, jughead, time’s awastin’ and Spark Plug” appeared on hundreds of American aircraft. Barney’s race horse “Spark Plug” was also a born loser and joined the crazy cast in February 1922, becoming a major part of the strip. In 1934, a much greater change took place when Barney and his race horse visited North Carolina and met a local moonshiner named “Snuffy Smith.” Snuffy lived in a shack in “Hootin’ Holler” and his last name was pronounced ‘Smif.” This moonshiner made “Corn-likker” and soon took over the strip becoming the main character. With the death of DeBeck in early 1942, the strip was taken over by Fred Lasswell, who had been assisting with the same cartoon creation since he was a seventeen-year-old artist.

This image was taken at Baer Field, Fort Wayne, Indiana, in early October 1942, just before the departure date for Goose Bay, Labrador. The man on the left is pilot 1st Lt. Grove Cleveland Hodge Jr. and on the right is his co-pilot 2nd Lt. Paul F. Jansen. This image was mailed to his parents by pilot Hodge, and sent for my research in 1983, from his sister Alma L. [Hodge] Rose. The left [port side] nose art on Marauder 41-17862 contained a nude lady with lettering “Mollie U” which has been confirmed by Newfoundland Ranger Gillingham, February 1994 research. These two nose art paintings were created and completed by Sgt. George Ruesh of the 320th Bomb Group, 441st B. Squadron at Baer Field, Fort Wayne, Indiana, late September 1942. The bomber was then transferred to the 319th Bomb Group and Pilot Hodge and Janssen flew to Baer Field, Fort Wayne to pick up their new Marauder. The bottom crew members were not part of the Lt. Hodge original crew, they were additions just for the ferrying flight of his aircraft, left is Cpl. F.J. Galm and right is radio operator Cpl. Bailey. Pilot Grover Hodge Jr. was the son of Baptist Minister Reverend Grover Cleveland Hodge, and I am sure he was not impressed with the nude lady painted on his new Marauder aircraft, an image he would not pose under or send home to his parents.

Crew of Martin B-26B-2 Marauder 41-17862

1st. Lt. Grover Cleveland Hodge Jr.

2nd Lt. Paul F. Jansen

2nd Lt. Emanuel J. Josephson

T/Sgt. Charles F. Nolan

Sgt. Russel Weyrauch

Cpl. James J. Mangini

Cpl. Frank J. Galm

In early October 1942, the seven-man crew of Marauder 41-17862 were just another rookie aircrew of the 319th Bomb Group, 440th Bomb Squadron. It is important to remember these young Americans have been rushed through basic training, they have only received nine weeks training, where others will be given a full fourteen weeks. They have not mastered the advanced powerful Marauder bomber aircraft, and they are not close to being molded into an effective fighting team. They will receive no training in arctic survival skills, or the type of winter weather they will encounter in the far arctic north. They are told, if they survive a crash landing in the sub-zero Atlantic waters, they will only live for two to five minutes in the sea ice. Today two 319th B.G. Marauder crews remain at the bottom of the Atlantic waters, the third was found on 9 April 1943, and they were called “The Lost Crew.”

Image of pilot Grover Hodge Jr, from his sister Alma [Hodge] Rose, 1984.

List of 440th Squadron [twenty] B-26B Marauders that departed for Goose Bay, Labrador, on 13 October 1942.

B-26B 41-17745 – Pilot Zimmer and Miller’s “Pretty Buggy.”

B-26B 41-17758 – Pilot Black.

B-26B 41-17761 – Pilot Brent and Stewart, “The Boomerang.”

B-26B 41-177?? – Pilot Bernard Allen, “Twin Engine Queenie.”

B-26B 41-17773 – Pilot Baker.

B-26B 41-17807 – Pilot Buchanan.

B-26B 41-17827 – Pilot Black.

B-26B 41-17831 – Pilot Buchanan and Morris on 27 January 1943. Tail #23.

B-26B 41-17834 – Pilot Robb and L. V. Miller, “Bomble Bee.”

B-26B 41-17838 – Pilot Murray and Whitney.

B-26B 41-17840 – Pilot Buchanabn, flew first mission 30 January 1943.

B-26B 41-17844 – Pilot G. Williams and Rauw, “US Mail.”

B-26B-2 41-17862 – Pilot Grover Hodge and Jannsen, “Times Awastin.”

B-26B-2 41-17887 – Pilot Weiss and Dean.

B-26B-4 41-18000 – Pilot Ramsey and Kress, “Reluctant.”

B-26B-10 41-18215 – Pilot Lt. Kress, lost 26 November 1943. Tail #86.

B-26B-10 41-18256 – Pilot Robb and Miller, “Big Fat Mama” took southern route to Africa.

B-26B-10 41-18266 – Took southern route to Africa, tail #82.

B-26B-10 41-18273 – Lost with pilot Lt. Masters, 11 July 1943.

B-26B-10 41-18275 – “Little Salvo.”

[Note – this list was completed in July 1983, and has not been revised, it may contain errors.]

The 319th Bomb Group were assigned B-26B Marauder aircraft from the serial blocks 41-17544 to 41-17624, 41-17626 to 41-17851.

B-26B-2 from serial blocks 41-17852 to 41-17946.

B-26B-4 from serial blocks 41-17974 to 41-18184.

B-26B-10 from serial blocks 41-18185 to 41-18334.

On the 13 October 1942, pilot 1st Lt. Grover Hodge Jr. recorded in his diary the take-off from Presque Island, Maine, in Marauder B-26B-2 named Times Awastin’. Next stop was 569 miles away at Goose Bay, Labrador, a land of ice, cold, blizzards, and the final resting place [Saglek Bay] for this seven-man crew. The first publication of the “Lost Crew” appeared in 1944, when Ivan Dmitri gave a brief account on page 234 and 235 of his book Flight to Everywhere. I was born in March 1944, and would not learn or read this WWII diary until 1981, thanks to a pilot friend named Roy Staniland.

This photo was taken in Quebec in the spring of 1979, and the man in the white coveralls [left] is the late Roy Staniland from Calgary, Alberta.

The photo was sent to me by his daughter Kathleen Staniland. Roy was one of the founding members of the original Aero Space Museum of Calgary, and the acting President in 1980, when I became a member. A year later, we had established an aviation friendship and I was welcomed into both his home and Petro Canada office at the Calgary International Airport. Roy was in charge of the Canadian Government Helicopter fleet [Petro Canada] which operated across Canada and had a western head office in the south side of the Calgary International Airport. Roy was hired for this important job partly for the experience he gained flying in the high Arctic during the 1950s and 1960s. Roy understood the demands of flying and surviving in high Arctic and Atlantic Ocean coastline of Labrador, Canada.

Roy flew many different aircraft in the Arctic equipped with wheels, skies, and floats. I soon gained a tremendous amount of respect for this Arctic bush pilot, as he shared his many flying adventures with me. I also learned Roy made trips to Newfoundland two or three times a year to inspect the performance of the helicopter fleet flying to and from the oil drilling platforms off the Labrador coastline. His air travels took him to Goose Bay, and then north to a very cold remote place called Saglek Bay, Labrador, “where an American bomber crash landed in 1942” he said. That’s all it took, and the following year [1981] Roy returned from Saglek Bay with a “Canadian” copy of the Diary of the American pilot 1st Lt. Grover Hodge Jr. which begins on 12 November 1942. Then I purchased USAAF records of the crash and their Diary copy, which begins on 13 October 1942, and contains a few minor differences from the Canadian copy.

For the next fifteen years, I completed detailed research on this crash site, the crew, and accounts of what took place. Roy Staniland became my onsite researcher, who took photos, walked around the crash area, and provided me with many hard to answer questions, which only an Arctic pilot would know. You will see why this was so important, later in my history.

In 1983, I made phone and letter contact with John and Alma Rose in Florida, as Alma was the sister of pilot Grover Hodge Jr. We became friends and they shared photos, family history, and a most important fact, the personal effects of her brother had never been returned to the family. In fact, her father, Reverend Grover Hodge [Senior] had been attempting to located these missing items during his life time, [passed away 1980] and now John and Alma had taken over this task, with negative results. The personal effects were a will, power of attorney, $71.00, his pilot wings, the family bible, a cornet, a Gruen wrist watch, a 35 mm camera with exposed film, her brother’s gold ring, and his pilot log book. These items were never recorded in the American files I obtained, [where many, many, lines had been marked out with a black pen] however the Canadian records contain all the true facts. I feel the material leading up to the crash and the aftermath of the forced landing may still be hidden in the files of the USAAF from 1942, and have never been properly researched. My research was conducted from 1981 until 1998, by phone calls, mail, archive records and major help from the following people. Mr. Robert H. Schamper, St. John’s Newfoundland, 1993, Mr. William Parrott Director of Crown lands, Newfoundland and Labrador, research maps and history of Labrador, 1994. Mr. Bill Parrott, St. John’s Newfoundland, who had visited over 100 military crash sites in Labrador and Newfoundland, 1994. Mr. Harold Horwood, Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, a most helpful person who shared his knowledge of the Labrador coast he had visited since 1949, research June 1993. The color slides of the crash site and area surrounding Saglek Bay were taken by pilot Roy Staniland in 1983.

Much has been written and published about this crash beginning in 1944, and continues today with a new book appearing in 2018. The hand written copy of the Diary has been published some thirty times in aviation magazine articles, newspapers, hard cover books, 319 B.S. newsletters, and now on the Internet. Throughout the past 60 plus years’ various articles containing insufficient information, with far too many inaccuracies and assumptions were also published.

My fifteen-year research has been in a box in my basement since 1998, and now I wish to share some of what I learned. Some parts will possibly shock or unset the reader, but I believe it is the truth, and maybe some American historian will continue where I have left off.

I do not have the space or time to present all of my old research, however I will concentrate on a few main areas which I feel need to be addressed. Labrador contains over a hundred aviation crash sites and a number of crew members are still missing, and may never be found in this cold barren land. Three crew members of Marauder 41-17862 “Times Awastin” have never been found, Josephson, Nolan, and co-pilot Jansen [right] in photo.

When the 440th B. Squadron arrived at Goose Bay, Labrador, 13 October 1942, only five of the previous three squadrons of 37 Marauder aircraft remained, awaiting repairs. Winter weather now closed in on Labrador with zero visibility, strong winds, snow, rain, and freezing rain at 300 to 500 feet. Only two days in the last two weeks of October allowed the squadron to fly east to Narsarsuaq Fjord in southwestern Greenland.

The Diary of pilot Hodge on 12 November 42, [Greenland] records the loss of 16 minutes of daylight every 24 hours, with around five hours of sun daily. The winter blizzard conditions at Greenland were much the same as Goose Bay, Labrador. On this same date, the Diary of the 319th B. G. records 36 Marauder bombers have landed in England, [beginning 14 Oct. – Horsham, St. Faith] nine have suffered from the winter ferry trip, damaged beyond repair, they can only be used for spare parts. Eight other bombers require major repairs and that leaves the 319th with only fifteen Marauders to proceed to North Africa. The 319th depart for North Africa on 21 November 42, and over France two more Marauders are shot down by German fighters, over Cherbourg, including the Group Commander. The twelve remaining Marauder bombers arrive at Tafaraoui, Algeria, on 24 November, and the 319th will fly their first combat mission on 28 November, with nine aircraft. [three from 437th, four from the 438th and two from the 439th Bomb Squadrons. The missing squadron [440th] are still trapped in Greenland [Narsarsuaq Fjord] with fifteen Marauder bombers, and the other five are still at Goose Bay, Labrador. The next stop of the northern ferry route is Iceland, which is now full of American bombers which cannot leave due to the weather. On 28 November 42, USAAF Command orders the northern ferry route closed and all aircraft located at Greenland will return to Goose Bay, the United States, and take the southern ferry route to Africa. The American aircraft stranded at Iceland will proceed to England when the winter weather permits. They will arrive in U.K. the first week of December 1942.

This was my book cover drawing I completed in 1985, for a possible publication.

On 10 December 1942, four Marauder bombers in the 319th B.G. took off at 13:15 hrs headed for Goose Bay, Labrador, which was 776 miles due west. The four aircraft were long overdue, [five hours] but then one Marauder lands at Goose Bay. This single crew made a tragic report that shortly after leaving Greenland, they suddenly hit a violent blizzard but were able to stay in sight of each other. Suddenly, and without warning the lead Marauder went into a spin and plummeted towards the ocean. Two of the bombers swung around and returned to Greenland, but only one arrived. The fourth continued on with the original course, became lost for some time, later found the Labrador coastline and landed at Goose Bay. At this date, it was reported that two Marauder bombers crashed into the Atlantic Ocean. On 9 April 1943, an Inuit hunter finds a Marauder aircraft and four bodies of the crew members at a place called Saglek Bay, Labrador. Saglek Bay is 376 miles [605 k/m] north of Goose Bay, Labrador. The pilot’s log book [Diary] gives his brief day-to-day story.

The Moravians of Great Britain sailed to Labrador in 1752 and established their first mission at Hopedale. Their leader Johan Christian Erhardt and five others were soon killed by the Inuit, and the survivors returned to England. In 1771, the British Government gave them 100,000 acres of land along the Labrador coast and they established their first mission at Nain. This was possibly selected as Nain is the end of the treeline and a division from Coastal to Tundra region. This is explained in detail on many websites if you are interested. Four years later they moved north and established Okak, and in 1782 re-established Hopedale the original landing site of 1752. In 1820, a large mission was established at Hebron and construction was not completed for ten more years. The mission at Hebron had several permanent buildings and one very large church with a common dwelling building which was constructed as one complete unit. All of these protestant fraternity missions were well marked on maps of Labrador in 1942, and supplied to American flight aircrews.

The following opinions are those of the author and many were obtained from Arctic pilot Roy Staniland from 1982-1984. Roy flew over the same route as the 1942 Marauder, took 35 mm slides, and proof read all my first draft material making necessary corrections.

Pilot Lt. Grover Hodge Jr. took off from Greenland at 13:15 hrs. 10 December 1942, became lost in a snow storm, dove to the ocean at 2,000 ft. and later in clear sky climbed to 13,000 ft. The least amount of daylight in the high Arctic is December and January with two to three hours. It is vital that the navigator in any aircraft shoots the sun during this period of daylight hours and keeps a constant check on the aircraft speed, drift, and position.

Navigator Carl R. Anderson [above] “Shoots the Sun” from a C-87 cargo aircraft flying over Labrador in December 1942. 2nd Lt. Emanuel Josephson was the navigator in the Marauder “Times Awaistin” however for reasons we can only guess, he could never find the aircraft true position. It appears pilot Hodge received one heading to Goose Bay and never requested other headings or corrections for the next three hours. When they hit the coast of Labrador they were still lost and had no idea where Goose Bay was located. The crew had spent three weeks in Goose Bay, which was constructed in a heavily forested area, but pilot Hodge was unfamiliar with the ‘treeless’ Tundra region of northern Labrador and flew north thinking they were still south of Goose Bay. Two fatal errors by both pilot and navigator, which would cost the crew their lives. In winter this Tundra region appears almost featureless in the white snow and it is impossible to determine the distance of objects or mountains. Pilot Hodge should have made a plan “B” but it appears he just flew north in hopes of sighting Goose Bay from the air. No trees, no Goose Bay.

It appears the Marauder flew as far north as Nachvak Fjord, which is 418 miles north of Goose Bay. Roy Staniland flew over this area in 1983, recorded photos and he believed the lost crew must have observed the very large mission building at Hebron, Labrador. This Hebron mission had a fluctuating population of 180 Inuit in the winter months, including five white residents, a Hudson Bay trader, an interpreter, two missionaries and one police officer, Newfoundland Ranger Gillingham. With his fuel tanks reading empty pilot Hodge turned around and flew south, possibly attempting to find Hebron for a crash landing, but we will never know.

It is almost dark outside and Hodge is looking for a forced landing site on the coastline as he flies south-east over Saglek Bay. Roy Staniland flew this route in 1983, and recorded this image of what was seen from the cockpit of the Marauder in 1942.

If you remove the aviation fuel tanks [foreground] and the landing strip, add winter snow, this is the spot Hodge picked to make his forced landing in 1942. Hodge flew south, made a right bank and force landed with wheels up on the rocky snow covered ground. The two engines began to cough for lack of fuel as he touches down and skids across the snow. Before stopping, the right propeller struck a large rock which spun the aircraft 360 degrees and one broken prop cut a hole in the fuselage behind pilot and co-pilot area. The crew were not injured. Navigator Josephson took a star shot and discovered they were 400 miles north of Goose Bay, Labrador. The crew understood they were near the mission of Hebron but had no idea where it was. Hebron was 30 miles due south from the Marauder bomber, but could not be seen from the aircraft, as some have reported.

The mission at Hebron was closed in 1959, however this huge structure still remains on sight. The crash site of the 1942 Marauder was straight over the church roof 30 miles north across the background mountain range. This Church is presently under a seven-year restoration program. Balsam poplar tree groves extend north to Napaktok Bay, and the low areas around Saglek Bay [green] grow forest tundra shrub vegetation and a few berry plants.

The online Diary of pilot Hodge gives many details such as 12 December 1942. They saw fifty seals in the north shore, and Hodge wrote they had food, but nothing was done to kill a seal.

1983 image by Roy Staniland showing the north shore bay area where seals were sighted. If they had shot one seal, it possibly would have saved their lives. On the same date, they constructed a living area under the Marauder main wing using the aircraft tarps. [below]

This 1983 image is looking south, the direction the Marauder came from and where it came to a stop, hitting a rock and spinning around to face south. The small lake is mentioned in the Hodge Diary, where they drank water, until one day it froze. In 1983, only the Marauder main wing skeleton remained near the roadway.

From November until April the pack ice freezes solid for ten to fifteen miles.

Hebron is the best seal hunting area on the Labrador coast and the Inuit people travel around the frozen shoreline with their dog teams. On 9 April 1943, one Inuit hunter discovered the snow covered aircraft and investigated, finding three bodies of the crew in their tent structure under the aircraft wing. He returned to Hebron and reported the find to Police Officer Ranger Bud Gillingham. Ranger Gillingham investigated the scene, and found a fourth American crew member outside the tent in the drifted snow. Gillingham recovered all the personal effects of the four crew members and returned to his office at Hebron, where he contacted American authorities, then filed his detailed reports. All the Gillingham reports are on file in the archives in Ottawa, dated 3 May, 31 May and 9 September 1943, Ottawa file connection 3-1-4. From Pilot 1st Lt. Hodge Jr., Ranger Gillingham removed $71.00 American cash, a will he wrote at the crash site, power of attorney, his family Bible, his pilot wings, one Gruen wrist watch, a gold ring from his finger, one cornet, one 35 mm camera with exposed film, and the pilot diary or log book. Major Norman Vaughan was the lead American investigator who flew from Goose Bay, Labrador, in a Norseman aircraft equipped with skies and landed on the frozen ice near the Marauder. The four bodies were removed along with a considerable amount of material in and around the bomber. Ranger Gillingham turned over all the crew personal effects, which were recorded in his reports. The four remains and material were all transported to Fort Chimo and that is the last time the crew effects were ever seen. The American reports from Major Vaughan remain silent on where or who the personal effects, 35 mm camera, and pilot log book [diary] were turned over to. The family relatives received no personal effects of their loved ones, or any explanation. Someone in the USAAF wanted these records destroyed, but why? Roy Staniland and I believe it was a U. S. cover-up to protect the possibility the three starving members resorted to cannibalism in an attempt to survive.

The Marauder 41-17862 remained in perfect condition until the United States Navy arrived at Saglek Bay in 1950 and began construction of the first American radar site. Thousands of American personnel were rotated in and out of the site, and hundreds of photos appear on the Internet today. For some reason only one image of the Marauder appears from 1951, showing the engines have been removed along with other sections of the bomber. By 1955, the bomber was gone and only the main wing spar remained.

This image was taken in 1957, and only the main wing spar remains. Today [2018] even less remains. Why did the commanding officer of the U. S. Air Force unit allow this to take place? The U.S. Government ordered it. The bigger question is where are the remains today in the United States, museum’s, officer’s recreational rooms? This aircraft was transported to the United States by ships of the U.S. Navy, and it appears even today no American officials wish to remember this lost crew, who could also be called the “Forgotten Crew.”

In the 1960s a cement memorial with a commemorative plaque was erected by members of the 924th ACW Squadron who manned the original radar site. They destroyed the Marauder aircraft the lost crew perished in, however they were the very first to truly honor the seven members. This original radar site was only manned by American military personnel, and was closed in the 1970s. In 1978, the United States decided to demolish the complete site and hired Canadians from Newfoundland to complete the task. A Canadian helicopter pilot from Newfoundland decided he wanted the brass plaque on the concrete cairn and had a bulldozer operator crack the base with his blade and the plaque was stolen. In the 1980s an American born [Nebraska] Wildlife Biologist was hired by the Government of Newfoundland and when he saw the damaged cairn and learned the memorial plaque was stolen, he was enraged. Mr. Stuart Luttich worked extensively on locating the brass memorial plaque and it was located in Newfoundland. The helicopter pilot had been killed in an accident, and his widow turned the plaque over to Stuart for return to Labrador. A new radar site had been constructed by the Canadian government, managed by Frontec Logistics Corporation, and they reinstalled the original plaque inside one of the new buildings [21 December 1989] at North Warning Radar Site Saglek Bay, Labrador. Today the original cairn has been repaired with a new plaque placed on it. The original brass plaque remains inside an onsite Canadian building, protected from theft.

On 23 December 1942, the three crew left by rubber lifeboat, navigator Josephson, Nolan, and co-pilot Jansen. The entry in log book of Hodge records –

“Got up at 07:15 hrs, got the boat ready and started carrying it. The wind was pretty strong and the boat was heavy, so we had a pretty hard time of it. We didn’t get to the water until noon and then it took quite a while to find a place to put it in the water.”

The Marauder came to rest much closer to the north shore and the south shore was located three times the distance from the aircraft. The ice covering the shore area would stretch at least five miles into the Labrador Sea, and that is why it took all day to get the rubber boat launched.

“We intended to put them off shore, but they appeared to be making headway to the south. That was the last we saw them. We had a hard time coming back across the snow. We had some peanuts and caramels and went to bed.”

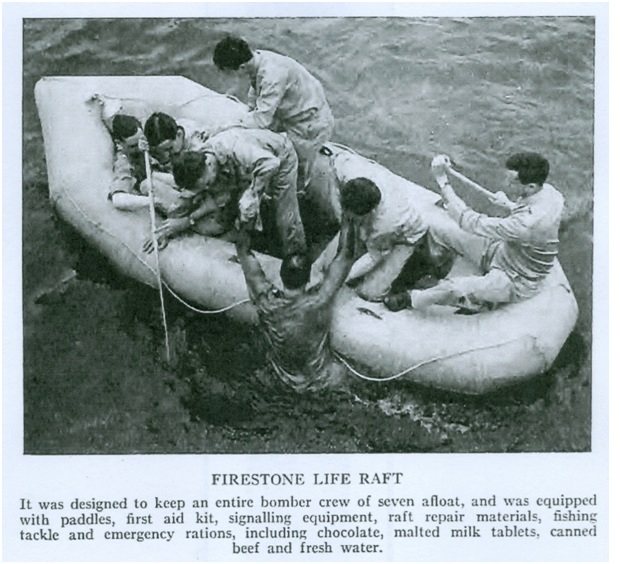

The Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, Akron, Ohio, manufactured the seven-man life boats which were carried in the B-26B Marauder. The three aircrew left with half the rations from the aircraft plus the rations carried in the rubber life raft. They were never seen again.

Roy Staniland and myself discussed the actions of the three aircrew in the rubber life raft many, many, times. The Labrador Sea current flows from north to south, and if they had good calm weather for three or four days, it was possible to travel 100 miles down the coast. Then if they made it inland to the treeline, they could shoot game, build a fire, and possibly survive for a period of time. Could there be any evidence to support this theory in Ottawa? Yes.

On 30 April 1943, the native Indians at Fort Mackenzie, Northern Quebec, find the tracks of three white persons, two on snowshoes, one on skies. The are proceeding south some seventy miles east of Fort Mackenzie, Quebec. On 3 May 1943, high powered rifle shots are heard by the native Indians, but the search of the area is not practicable. I attempted to obtain records from the American Base at Fort Chimo, Quebec, but no luck. It was in fact impossible.

The WWII airfield at Fort Chimo, Quebec, [now called Kuujjuaq, Quebec] was constructed in summer of 1942, with permission of the Canadian government. This was a proposed joint American-Canadian ferry route base known as the “Crimson Project” to transport American aircraft from California to Europe. This Arctic route had code names and Fort Chimo received the code name of Chrystal One and was manned by the American U.S.A.A.F., no Canadians involved until 1955.

I believe the three crew in the life raft proceeded some 75 to 100 miles down the coast of Labrador, then realized they would never survive in the Atlantic Ocean. They were somehow able to make it ashore and proceeded south-west in the direction of Fort Mackenzie. Once they found the treeline they also found game to shoot, build a fire, and survive. This was very deep snow in winter time and it took them three months to come within 70 miles of Fort Mackenzie. Today their bodies remain somewhere south of this only reported sighting. The two sets of snowshoes and one of skies remain a puzzle, how were they obtained?

This is a 1950’s image of the mission at Hebron and in the foreground is the small white living quarters and office of Newfoundland Ranger Bud Gillingham. This is where he took the personal property of the four deceased American Marauder crew and typed his detailed reports which are located in Ottawa today.

The USAAF purchased and operated over 800 Canadian built Noorduyn Norseman aircraft during WWII. Norseman UC-64A, serial 43-5113 was delivered to the USAAF on 26 February 1943, flew Alaska 1 May 43, crashed 26 July 1944. Sold postwar to J.E. Jack, Miami, Florida. This is the same type of Norseman on skies, which flew into Hebron, Labrador in April 1943. Between 11-22 April 43, this American UC-64A made four trips from forced landing site to Fort Chimo, Quebec.

On 11 April 43, Major Vaughan, Lt. Holmes, and Lt. Norton flew from their American base at Goose Bay, and landed their UC-64A with skis on the frozen ice in front of mission Hebron. They picked up Ranger Gillingham and flew to the Marauder forced landing site 30 miles north, landing on the ice at the north side of Saglek Bay, Labrador. That’s when and where the American investigation began and Major Vaughan had his first look at the four aircrew bodies. This was all recorded on 35 mm film, but it appears all was destroyed. By 22 April 43, all the evidence from the crash scene and the four bodies had been removed by Norseman UC-64 ski plane to Fort Chimo, Quebec. [a number of flights] If the 1943 reports at American Base Fort Chimo, Quebec, survive, they should contain important information. The 35 mm camera from pilot Hodge, with exposed film, was developed at Fort Chimo but neither the photos or camera have ever been located.

Major Norman Vaughan was an expert on the Arctic, and most important American aviation V.I.P. Just Google his name and you will be surprised what he has accomplished during his life-time. In the 1990s he was involved with the early recovery of the B-17 bombers and P-38 fighters they found 260 feet under the ice in Greenland. John and Alma Rose [sister of pilot Hodge] made phone contact with Norman Vaughan at his home in Alaska, and guess what. He could not answer any of their questions in regards the missing personal items from her deceased brother.

In February 1994, I attempted to make phone contact with Newfoundland Ranger Bud Gillingham, living in Norris Arm. He was in his 90s, almost blind, deaf, and suffered from diabetes, so I could not bother him. His reports and the records of his superior Chief Ranger Captain E. L. Martin are on file in Ottawa. So, why have the American most senior officers destroyed their records and facts on this forced landing? It’s just another wartime crash in Labrador, right? Then there was no rational reason the USAAF would destroy so much evidence, including the Marauder the crew flew. Very senior USAAF officers read the Hodge Diary [log book] and then it disappears forever.

For anyone interested, the RCAF and RCMP file reports on the three white persons 70 miles south-east of Fort Mackenzie, 30 April 1943, can be found under –

PAC Reference: Record Group 24,

Volume 18, No. 114, file 976-3

Part Two – Goose Bay, 1008-1-125 [D/AMAS-Ops]

It is very likely the rubber carrying bag, which contained the un-inflated rubber life-boat was used to carry the rations by the three men in the life boat. This should possible be found with the bodies it they are ever discovered. There is much more research required to learn the truth of this sad story, and preserve history. What took place at Fort Chimo, Quebec, 11 to 22 April 1943, may never be known. I have done my best to learn the truth, of course, it is still the business of the United States government and U.S. Air Force to decide if the truth is ever told.

The Firestone Life Raft was stamped with a serial number and the name “General Tire and Rubber Co. Akron, Ohio.” The raft was contained in a rubber carrying bag also numbered and marked Property Air Force U.S. Army. The bag was stored in a section of the upper fuselage on the port side right next to the crew emergency escape hatch.

The early rush to form the 319th Bomb Group and the lack of proper aircrew training cost American lives and aircraft. I have attempted to show this in my research taken from original unclassified reports. Originally assigned 57 new Marauder bombers, the 319th flew them to Goose Bay, Labrador, and only 36 would arrive in England, beginning 14 November 42. Nine were scrapped, eight required major repairs, and only 14 departed for Algeria, North Africa, on 24 November. Two were shot down in France, and the 319th entered combat with only twelve Marauder B-26B aircraft. The twenty Marauders of the 440th Squadron were stranded in Greenland and ordered back to the United States. Three of these crews were lost, and only five of these B-26B bombers reached North Africa. Out of 57 original B-26B aircraft, thirty were lost containing 35 aircrew members, and they have not gone to war. One of these Marauders contained the nose art of “Smilin’ Jack’s” girlfriend Dixie Lee. This bomber flew into Goose Bay, Labrador, 13 October 1942, but that is all of the known history. The Marauder serial number is not known. This bomber and crew could remain at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean today.

I always wondered if Zack Mosley had created this original art or if it was just from the brush of Sgt. George Ruesch of the 320th Bomb Group.

In 2000, I phoned Jill Mosley and we enjoyed a nice chat, which included my many questions. Her father Zack was born in Hickory, Oklahoma, 12 December 1906, obtained his pilot licence on Friday 13 of November 1936. During his life-time he owned and flew nine aircraft, logging over 3000 hours. He flew as a volunteer pilot in the Civil Air Patrol and during WWII flew 300 hours of patrols in bomb-loaded civilian aircraft, patrolling the Atlantic coast. He created the wartime insignia of the Civil Air Patrol pilots, featuring a Gremlin with wings. [still can’t find an image] He studied art at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts and created “Smilin’ Jack in 1933, which ran until 1 April 1973. He was personal friends with Jimmy Doolittle, and astronaut Ed Aldrin. He designed aviation posters, and program covers for many flying events. Zack passed away in 1994 at age 87 years.

I explained I was looking for any drawing of Smilin’ Jacks girlfriend Dixie Lee, and she would be flying fully nude with two propellers on her breasts. Jill replied she would look, but it would take time, she had all of her father’s original drawings from 40 years, and this amounted to over two thousand images. In February 2001, an envelope arrived by mail and what a surprise.

In September 1942, someone in the 320th B. Group wrote to Zack Mosley requesting a nose art image of Dixie Lee. This was mailed to the member, given to nose artist Sgt. George Ruesch who painted Dixie on the Marauder. The Marauder was next transferred to the 319th and flew off to Goose Bay, Labrador.

The 319th Bomb Group was reborn in North Africa and at least sixteen of their Marauder completed 100 or more missions.

This was the second “Twin Engine Queenie” with no name painted on her nose. The serial number 41-34895 can be seen in photo and she flew in the 440th Bomb Squadron with tail number 72. Transferred to the 17th Bomb Group she received tail number 76.

On 14 August 1944 she had completed 73 missions and hit 100 the following month.

The little nude “Dixie Lee” became the seventeenth B-26 Marauder in the 319th Bomb Group to complete 100 missions. Smilin’ Jack would have been proud; I know Zack Mosley was.

In May 1942, the original [log book] diary of B-26B pilot Lt. Grover Hodge Jr. arrived in Washington, D.C. and was read by many senior USAAF officers. They fully understood the problems ‘they’ created by rushing untrained air force crews into combat and the need for aircrew survival training. On 15 July 42, the USAAF established a new B-26 Marauder replacement training school by the Third Bomber Command, 336th Bomb Group, at MacDill Field, Florida. The first Commanding Officer was Lt. Col. Josha T. Winstead, and I’m sure he read the original diary of Lt. Hodge Jr.

USAAF graduates from this new school received technical instruction, gunnery, and B-26 Marauder twin-engine flight training, plus instructions on how to survive in water, jungle, and arctic conditions. A new USAAF survival manual was published and received by all air crews, which was the beginning of the Strategic Air Command special survive and avoid capture training established on 16 December 1949.

The original Marauder school was inactivated on 1 May 1944 at Lake Charles Air Force Base, La. The USAAF then pulled together an assorted group of arctic pilots and survival experts at Fort Carson, Colorado, in 1947, and from these meetings the 3904th Survival Training School was established. That’s where the original dairy of Lt. Grover Hodge Jr. came to an unknown end.

This research is dedicated to the memory of the “Lost Crew” and John and Alma Rose, who gave me all their history, friendship, and support.