This is the front cover of the Royal Air Force “Official Programme” for Saturday, May 20, 1939, Empire Air Day. This would be the last Empire Air Day before the beginning of World War Two. This copy was found in an old book store in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, in the mid-1980, and the front cover contains the signature of Squadron Leader D. H. Carey, who was the R.A.F. Press Liaison Officer for the Empire Air Day, Acklington. The Flying Program has 66 pages, cover to cover, and while the front page of the issue features the color art of three Hawker Siddeley Hurricanes, the contents of the programme are mostly directed at the possibly of war with Germany, the new Vickers Supermarine Spitfire fighter, and the powerful Rolls-Royce Merlin engine.

The original Supermarine Company was formed in 1912 at Southampton, with main offices in London. They were chiefly devoted to the production of British sea-going aircraft, and specialised in the design and production of high speed seaplanes. They entered and won the 1922 contest at Naples with a Supermarine Sea Lion reaching an average speed of 146 m.p.h.

All Naval aircraft ordered for the British Fleet Air Arm were given the prefix “Sea” such as Hawker Sea Hurricane, Supermarine Sea Spitfire, etc. In 1927 two Supermarine S.R seaplanes came first and second with speeds of 281.65 and 273.07 m.p.h. In November 1928, Vickers Aviation, Ltd. took over control of Supermarine Aviation Works and the name [Vickers] was added to the title. In the 1929 contest a Vickers Supermarine S.6 won with an average speed of 328.63 m.p.h., and later set a world speed record of 357.7 m.p.h.

Supermarine S.6B, S1596 (Public Domain)

This Folland Aircraft ad appeared on page 62 of the 20 May 1939, Empire Air Day programme.

In 1933, a Vickers Supermarine single-engine, Amphibian Flying Boat appeared with the name Seagull V, and a number were sold to the Australian government under that same name. In 1934, the Seagull was being adopted for Royal Navy ships equipped with catapults and employed in training, communications, and Air-Sea rescue duties. When the British Admiralty ordered an aircraft from the manufacturer, they were given nautical theme names, thus the Seagull was renamed the “Walrus” and produced in two versions, the Mk. I with a metal-hull and the Mk. II fitted with a wooden hull. A second twin engine seaplane [flying boat] prototype was being constructed at the same time, but only seventeen were produced, and future orders were cancelled. British flying boats were given names of coastal towns or ports, and the new aircraft was named after a coastal town in southwest Scotland, on the shores of Loch Ryan, Stranraer, Scotland. Historians give many reasons for the cancellation of the Stranraer production, but the main fact remains the British Navy just did not want them, they were already obsolete.

In March 1936, the Vickers Supermarine first landplane prototype flew, and soon the new “Spitfire” fighter went into full production, and we all know the rest of that history. While the seventeen British built Vickers Supermarine Stranraer flying boats should have remained a seaplane from the past, Canadian Prime Minister W.L. King would give it a new life, soon after he came to power in October 1935. In July 1936, King organized a Cabinet Defence Committee to outline the government’s new policies. The political wheels of change turned oh so slowly, but is was very clear the thirty-one obsolete aircraft of the RCAF needed to be upgraded, to provide any form of air defence in Canada. By the end of 1936, P. M. King had decided the RCAF must become the Dominion’s first line of defence, and that required more spending. Canada’s defence budget for 1937 would double to $5 million and again in 1938, this would climb to $9 million. It took a lot of political courage to make the right decisions, as the Canadian Government Liberal party under King could not yet commit itself to fighting alongside Great Britain in the event of war. Sixteen Quebec Liberal MPs had already rejected the new defence budget for the simple fact they did not want any French-Canadian money spent in defence of Great Britain. All the money must be spent exclusively for the defence of Canada, and this caused hostile battles in some elements of the Quebec press and the isolationist public opinion in a good part of Quebec. P.M. King had to walk a tight-rope with his own Quebec MPs, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation [CCF] and the rest of English speaking Canada. [These same modern fighter political cost problems affect our RCAF aircraft today] The Canadian Government wanted to buy around a hundred modern aircraft, with the majority used for coastal surveillance and torpedo bombing. However, the prime minister was horrified by the potential cost of the new RCAF rearmament program, and this would limit their choice of aircraft. Another problem became the choice of what country to purchase from, which involved a compromise: buy American and face a possible embargo if war came, [American remained neutral and would pass neutrality laws in event of war in Europe] or purchase from Great Britain, and face major political problems from his own government MPs in Quebec. Air Commodore Croil, who was in charge of RCAF equipment and aircraft, recalls King wanted to purchase British production aircraft and the solution was not to buy British, but purchase the licence to produce the British aircraft in Canada, at Montreal, Quebec. This idea was approved by the Canadian Cabinet and history was made. Most of the Liberal MPs from Quebec were at last happy, as the French/Canadian tax money was being spent to produce RCAF aircraft built in Montreal, giving jobs to French-Canadians, and at the same time the RCAF rearmament program was not needed, which saved budget spending. King also hoped by awarding aircraft contracts to Montreal, the manufactures would gain experience in building large-scale production aircraft, which in the event of war, possibly would help unite Quebec with the rest of Canada. Now that the Canadian Government had created an aircraft acquisition policy, the next step was to decide which British aircraft were best suited to Canadian flying conditions and location in Canada. This should have been a no brainer, as the decision to purchase the best British aircraft to meet the RCAF requirements was in practice to be selected by air force experts. However, the British Air Ministry were also asked to recommend a reliable and effective aircraft, even when they had no idea what type of Canadian weather or flying conditions it would be required to operate in. Under a cloud of secrecy, Prime Minister King created a special interdepartmental committee to study the aspects of the new rearmament policy, and this was made up of members of the National Revenue, National Defence, External Affairs, and representatives of the Finance committee. The Liberal cabinet next created another political Interdepartmental Finance Committee on Profit control, made up of five departments, and so on.

The rearmament of the RCAF must be conducted without speculation or excessive profit, and out of this Canada obtained the license to build the British Vickers Supermarine Stranraer in Montreal, Quebec.

The immediate government priority was to equip and train nine RCAF squadrons for protection of the two large coastlines in Canada. It is impossible today to understand the Liberal government thinking, but the facts show most of their policies and British choice of aircraft were quickly or already outdated and obsolete when Canada went to war. It simply appears the Canadian government was attempting to build up their obsolete Air Force as quickly as possible, for a peacetime establishment, and a vital part of the complete aircraft rearmament was in keeping a low budget cost. In November 1936, the first order for five Stranraer seaplanes was received by Canadian Vickers Ltd. in Montreal, cost $28,000 per aircraft. The first two Canadian built Vickers Supermarine Stranraer flying boats were delivered in November and December 1938, assigned to No. 5 [General Recon.] Squadron at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia.

No. 5 Squadron was formed as a Flying Boat Squadron at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, on 16 April 1934, by amalgamation of five other Maritime Detachments, No. 8 to No. 12. They were primarily used by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to fly anti-smuggling and illegal immigration patrols until the RCMP formed their own air division in 1936. The squadron was then used for flying boat training and coastal duties until it was predesignated a Coastal Reconnaissance Squadron [1 April 1937] and later a General Reconnaissance Squadron on 1 December 1937. [The Squadron Daily diary]

The first five Canadian Vickers Supermarine Stranraer flying boats were taken on charge by No. 5 [G.R.] Squadron on the following dates: Stranraer #907 – [CV184] 9 November 1938, Stranraer #908 – [CV185] 3 December 1938, Stranraer #909 – [CV186] 11 May 1939, Stranraer #910 – [CV187] 30 May 1939, Stranraer #911 – [CV188] 8 June 1939.

On 10 July 1939, three [peacetime] defence patrol areas were created, “A” Yarmouth, “B” Halifax, and “C” Sydney, Nova Scotia. The division point between “B” and “C” was Cape Canso, Nova Scotia.

The Second World War began in the early dawn of 1 September 1939, when German Armies swept across the border into Poland. Great Britain, France, and Newfoundland, declared war with Germany on 3 September 1939. Newfoundland was not a province in Canada, and was ruled and administered by Great Britain, and yes, they were officially at war with Germany seven days before the rest of Canada. The Canadian Parliament met on 7 September 1939, and it took them two days to approved Canada would support Great Britain and France in declaring war on Germany. You must remember there was still a great deal of opposition in Quebec to support anything British, but the fact France had declared war along side Great Britain, allowed the motion to pass with support of the Quebec M.P.s. Then the Canadian Prime Minister [Mackenzie King] was required to ask the other “King” of England, [King George VI] to declare war for Canada. Yes, if you are still interested, we the colony, could not declare war ourselves in 1939, and it’s all there to read, but confusing and appears stupid in today’s world. On 10 September 1939, King George VI, announced [the second King’s Speech] that Canada had officially declared war on Germany, and now the Canadian taxpayer would have to start all over, and re-equip its Home War Establishment RCAF Squadrons with more modern aircraft, which would take time and cost tens of millions of taxpayer dollars.

The No. 5 [GR] Squadron Daily Diary for 1 September 1939, records the actual understrength of fifteen officers, sixty-three airmen, which should have been 24 Officers and 139 airmen. They are flying five Canadian built Vickers Stranraer flying boats [serial recorded] and four Fairchild 71 float planes, serial 630, 633, 639, and 640, which were taken on strength from November 1934 to September 1938.

This is Fairchild #630 float plane which was obsolete in defending any Canadian coastline in war or peacetime. On 7 September 1939, the Canadian Parliament approved going to war against Germany. No. 5 [GR] Squadron had available 17 pilots, 1 airman, three air-gunners, and nine obsolete seaplanes. Need I say anything more?

While the already obsolete Canadian Vickers Supermarine Stranraer was under construction in Montreal, the RCAF required hundreds of new recruits to be posted to Eastern Air Command, which became the lowest for RCAF priority of personnel postings.

Slowly new RCAF recruits of all form [truly the long, and the short, and the tall] were being posted to Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, and the beginning of training in No. 5 [G.R.] Squadron flying the Canadian Supermarine Stranraer flying boat. The authorized Canadian Government establishment for the peacetime RCAF on 7 September 1939, was 7,259 officers and airmen, but Canada had just over half that number when it went to war, with 4,153 officers and airmen on total strength. Defending the East coast of Canada appeared logical on paper, but putting those ideas into practice would take time and it was not that easy, as No. 5 [G.R.] Squadron would soon learn.

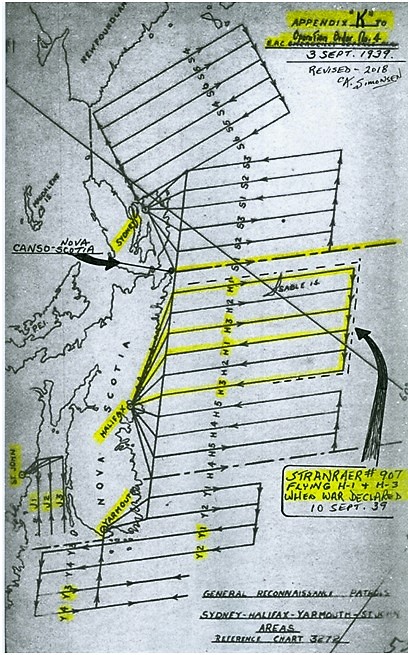

Eastern Air Command, Home War Establishment, Copy #1, Order No. 4, September 3, 1939, contained 41 pages of maps and detailed information with secret pre-war orders. The Declaration of War came seven days later, while the RCAF and our Canadian government did not yet fully understand the extent German submarines would threaten the Atlantic shipping convoys and lifeline to United Kingdom.

The four new revised pre-war patrol areas in Eastern Air Command, 3 September 1939. St. John, New Brunswick [J] – contained three areas, Yarmouth – 4 patrols, Halifax – 5 patrols, and Sydney – 6 patrol areas. The village of Canso, [Cape Canso] Nova Scotia, [45* 20’ 2’ North – 60* 59’ 43’ West] became an important reference point. Stranraer #907 was flying patrol H-I and H3 when Canada declared War on Germany.

The 3 September 1939, Eastern Air Command patrol areas at Gaspé G-1, G-2, and G-3, and one at Red Bay, Labrador. On 3 September 39, Newfoundland and Great Britain were officially at war with Germany, while Canada was still doing her political infighting over declaring war.

Supermarine Stranraer #907 taken on charge No. 5 [G.R.] Squadron, 9 November 1938. RCAF image #3651067. Being flown on coastal patrol [Halifax, H-1 and H-3] by F/O Birshall during first hours of World War Two.

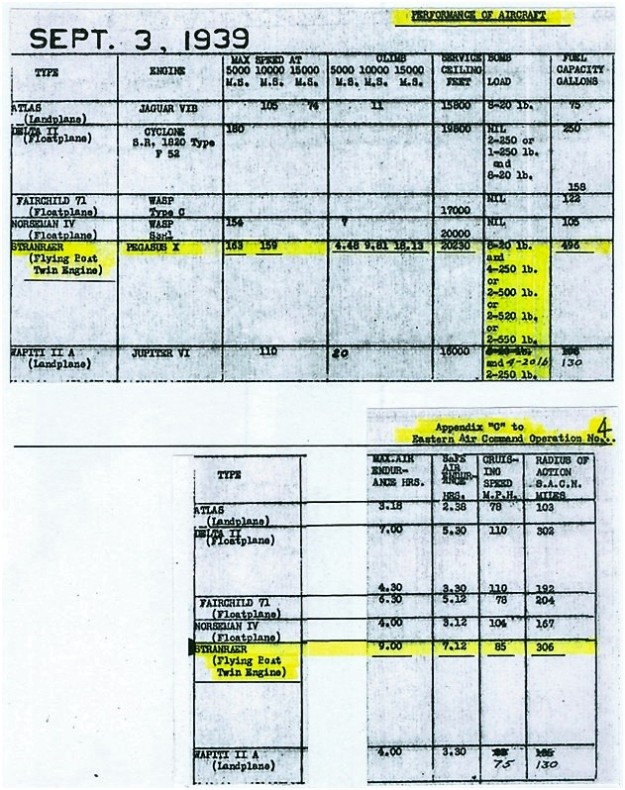

The selection of mostly obsolete RCAF aircraft Eastern Air Command had on strength entering WWII.

From Daily Diary of E.A.C., Halifax Nova Scotia, 3 September 1939.

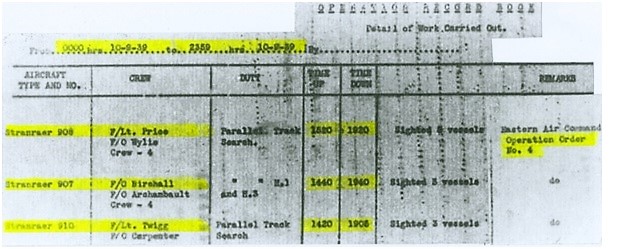

At 16:34 Hrs, [4:34 p.m.] 10 September 1939, No. 5 [G.R.] Squadron was officially at War, and three Stranraer flying boats were in the air on patrol. [#907, #908, and #910]

Today it is very clear RCAF Eastern Air Command was not prepared for anti-submarine attacks and could only provide air reconnaissance [Scare-Crow patrols] and report to surface ships to attack any submarine. These first operational squadrons of Home War Establishment were at the bottom of the priority lists for all essential RCAF personnel, equipment, trained aircrew, and modern aircraft. For the next twelve months, No. 5 [changed to Bomber Reconnaissance Squadron on 31 October 1939] [B.R.] would fly anti-submarine patrols from [Halifax] Dartmouth, N. S., Sydney, N. S., and Gaspé, Quebec. Historians have titled this period of time RCAF “Scare-Crow” patrols. Canada and RCAF Eastern Air Command were very lucky Admiral Donitz’s U-boat packs were not within striking distance of Newfoundland until one year later, September 1941. The first Halifax convoy memorandum #0188 was received by No. 5 [G. R.] Squadron on 15 September 1939, and makes for interesting reading, plus it is packed with historical facts. The first convoy put to sea on 16 September 1939, forming a pattern which was established for all other future ships sailing from Halifax harbour. The first full year of war, 1940, would be a time of trial and error, which placed rigorous demands on RCAF aircrew, ground crew, and their obsolete Stranraer flying boats. Their first patrol [16 September 1939] became a total disaster.

The next pages record the Daily Diary for No. 5 [G.R.] Squadron and her seven Stranraer flying boats [#907, #908, #909, #910, #911, #913 and #914] on 16/17/18 September 1939. New arrivals Stranraer #913 and #914 was taken on charge 8 September 1939. [built 5 & 31 August 39].

RCAF official image of Stranraer #913, [QN-B] taken on charge 8 September 1939, and flew on 17 September 1939 patrol, but failed to make contact with the convoy. S/L R.C. Mair in #911 became lost, ran out of fuel and made a forced landing near Cabot Strait. Stranraer #911 was lost during the recovery attempt at sea.

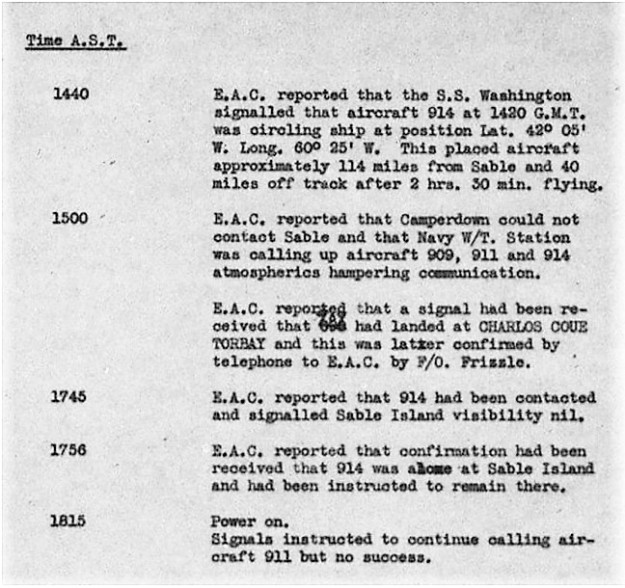

The Daily Diary for 17 September 1939, No. 5 [G.R.] Squadron gives all the facts which are not pleasant to read. The Stranraer Flying Boats leave on patrol to give air protection for the first convoy heading for England. Stranraer #908 returns to base, can’t find Sable Island. Stranraer #910 returns to base, can’t find the convoy. Stranraer #914 gets lost, and begins to circle a Canadian Navy Ship. It is 114 miles from Sable Island, and forty miles off track. Stranraer #911, also gets lost, runs out of fuel, force lands, and the flying boat sinks during recovery attempts. The Canadian Navy and the first convoy sail on without any RCAF air protection, but I’m sure the air was ‘blue’ at a few RCAF headquarters buildings.

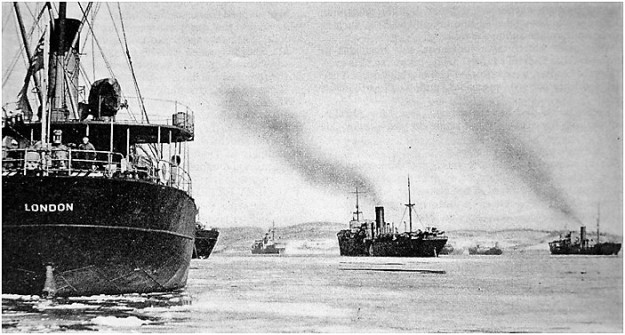

Five convoys sailed for England in October 1939, total of seventy merchant ships. This could be an image of one of those convoys, however the date is not recorded.

From Canadian MacLean’s magazine March 1942

The ice is forming in Bedford Basin, as the merchant ships await their sailing date. The first three convoys were not given a number, with the first H.X. #1 appearing on the convoy which sailed 25 September 1939. H.X. was the code assigned to Halifax to United Kingdom, and many new codes were now assigned for slow, fast, convoys proceeding to U.K.

No. 5 [G.R.] Squadron photos taken from Stranraer of convoy leaving Halifax late October 1939, which were numbered H.X. #3, #4, #5, #6, and #7 departing 1 November 1939.

In October 1939, you can clearly see Commanding Officer S/L A. D. Ross is making many changes in the area of navigation, [new log sheets] record of patrol map drawings, and three flights are created.

Each Stranraer flying boat must now submit a pilot “Track Chart.” The Stranraer carried maximum 1000 lbs of bombs, and on paper had a range of 1,080 miles, empty. In actual operations, the armament, equipment, and aircrew weight significantly reduced the old Stranraer performance to 540 miles, while the Canadian east coast weather conditions also greatly reduced the days this 1934 flying boat could even get into the air. As recorded on the anti-submarine patrol instructions, Stranraer flying boats accompanied all departing and arriving Halifax ship convoys, with safe flying time of five and one-half hours, for each dawn to dusk patrol. The maximum safe endurance of a Stranraer with 1,000 lbs of bombs was 6 hours, cruising speed of 90 mph. Needless to say, the Canadian government had selected the wrong flying boat for the anti-submarine task ahead, and now new modern aircraft would have to be purchased, or built in Canada under licence. The modern aircraft search turns south to United States.

On the 27 of October 1939, No. 5 Squadron began daily 07:00 hrs. harbour-entrance patrols, where the Stranraer proved to be a sturdy and dependable short-range reconnaissance flying boat. [Below] is the original “Harbour Entrance” patrol route for October 1939, only color has been added. The patrol began south of Halifax and zigzagged north, then returned over the same route in reverse. The red area, entrance to Halifax harbour was a Top Priority patrol section.

In November 1939, the Stranraer flying boats of No. 5 Squadron flew four Outer Convoy patrols, [H.X.#7, H.X.#8, H.X.#9, and H.X.#10, leaving on 1, 10, 18, and 25 of the month, totalling 117 ships on route to England. They also completed three special constant protections [meeting new arrival warships and flying overhead until the ships docked] for H.M.S. Warspite, and H.M.S. Effingham, on 14 November, H.M.S. Alaunia on 7 November, and H.M.S. Furious [Fleet Aircraft Carrier] and H.M.S. Repulse on 3 November, a “very special” constant patrol with one Royal Canadian Navy escort. This is the original reconnaissance report from Stranraer #914, [QN-O] from “C” Flight of No. 5 [B.R.] Squadron, pilot S/L A.D. Ross, the Commanding Officer, [until 26 July 1940]. Take-off time was 06:00 hrs on 3 November 1939.

Enter a caption

H.M.S. Furious [Aircraft Carrier] and Repulse were both sighted at 06:20 hrs. and a zigzag course was flown over the two warships until they entered the Halifax harbour and docked. Stranraer # 914 then returned to base, arriving at 08:20 hrs, patrol was 2 hrs., 20 minutes. For each convoy or special air reconnaissance a “Track Chart” must also be completed by the pilot of the patrol. Attached is the original Track Chart completed by C.O. S/L Ross and his special escort patrol on 3 November 1939. The Fleet Aircraft Carrier HMS Furious had been dispatched to Halifax with four British warships to escort the first Canadian Troop Ship [T.C. #1] to England. This troop convoy of five ships left Halifax on 10 December 1939, carrying the 1st Canadian Infantry Division to England, containing 12,543 troops, who safely arrived on 17 December 1939.

This is the original Track Chart for meeting British Fleet Aircraft Carrier HMS Furious and Battlecruiser HMS Repulse, and only color has been added by the author. This was the first aircraft carrier No. 5 Squadron had seen and photos were taken.

This official list contains many famous warships from WWII and a most famous troop ship from the Cunard Line, S.S. Aquitania. Her origins lay in the rivalry between the White Star Line and the Cunard Line. The White Star Line, [Titanic] were larger in size and more luxurious in design than the Cunard Line. Cunard constructed liners for speed and passenger safety, and in the wake of the Titanic sinking, the Aquitania became the first liner to carry enough lifeboats for all passengers and her crew. Aquitania was launched 21 April 1913, making her maiden voyage to New York, on 30 May 1914, arriving on 5 June. On her return voyage she hit a top speed of 25 knots, [for a short period of time] and carried a record 2,649 passengers from New York to Liverpool, England. During WWI, she was removed from service for six years, converted to a hospital ship [1916], and then in 1918, she became a transport ship, making nine trips from Halifax, Nova Scotia, transporting 60,000 troops to and from England. The troop ship was painted in a dazzle camouflage paint scheme, which has been captured in many paintings and photographs. The full career of this famous liner can be found on many websites, and is worth reading. In 1939, the Cunard Line planned to scrap the Aquitania; however the Second World War gave her a second career in again transporting Canadian troops to England. Painted in full Grey she now returned to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and once again transported over 8,000 Canadian troops, [per trip] to United Kingdom.

Above is the famous S.S. Aquitania converted to a transport ship, taking Canadian troops to England from Halifax, 1918. Just love the WWI camouflage painting.

The RMS [Troop Ship] Aquitania taking Canadian troops to England in December 1939.

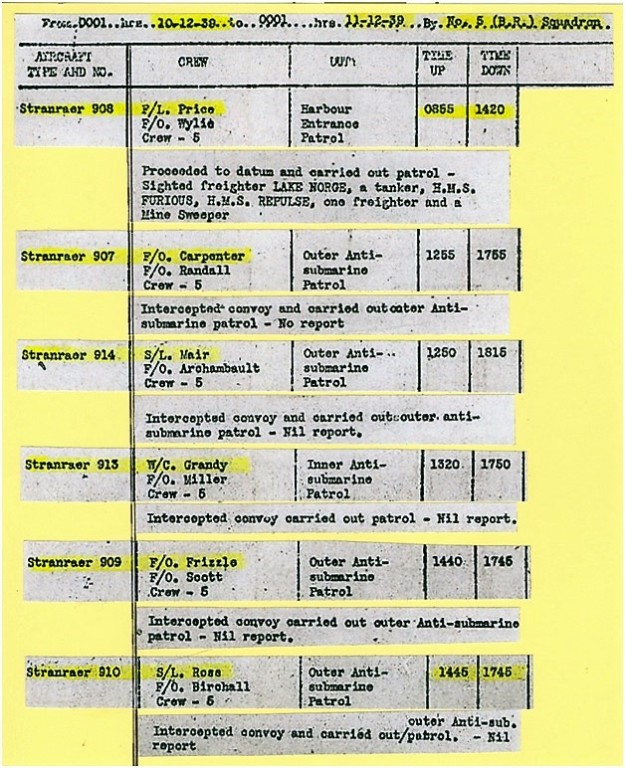

All six No. 5 [B.R.] Squadron Stranraer Flying Boats take part in the protection of Canada’s first Troop Convoy to United Kingdom, 08:55 to 17:45 Hrs. 10 December 1939.

This undated image shows Stranraer #914 [QN-O] patrolling over a merchant ship leaving Halifax harbour. MacLean’s Magazine March 1942.

The day before the Canadian Troop Convoy set sail from Halifax, [9 December 39] five new Hudson aircraft from No. 11 [B.R.] Squadron conducted patrols in sections H-1, H-2, H-3 and H-5 in front of the harbour. The aircraft were RCAF Hudson #761, #762, #763, and # 764, which had arrived at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, on 3 November 1939. These were the very first modern American coastal patrol aircraft to arrive at Eastern Air Command, and the beginning of major changes in aircraft and training for the coming U-boat wars.

This Lockheed ad appeared in September 1941 issue of LIFE magazine, author collection.

Historians have described the Senior RCAF officers of Eastern Air Command as being overly “parochial” [focusing on small issues and avoiding the reality of the growing U-boat war] and too often failed to get their priorities in proper order. They entered the war dependant upon British outdated aircraft, [Stranraer] poor communication equipment, and took months to adapt to new refinements which had been battle tested by RAF Coastal Command. At first the RCAF was most reluctant to adapt to the fundamental principal of British anti-submarine war, which changed repeatedly and rapidly. No. 5 [B.R.] Squadron had to coax their under-powered Stranraer flying boats to exceed normal limits of performance, in the worst flying conditions in the world. This has all been recorded in the squadron Daily Diary, and a new modern patrol aircraft was needed as soon as the Canadian government could find and purchase them. In England, their government was confronted by the new modern expanding German Luftwaffe, which was also larger than the RAF, and the British were forced in 1938 to turn to the United States for modern aircraft.

In July 1938, the British Purchasing Commission sought an American maritime patrol aircraft to protect the coastal areas of the United Kingdom. On 10 December 1938, Lockheed demonstrated a modified version of the Model 14 Super Electra airliner to the British government and 350 were ordered as the Hudson Mk. I and 20 more as a Mk. II. Above is a photo taken by LIFE magazine showing the construction of thirty-two new Hudson Mk. I aircraft at the plant in Burbank, California. The nine aircraft on the right are ready for shipment to England, by merchant ships.

The British Hudson order was so large, [370] these RAF bound aircraft had to be constructed outdoors, working around the clock. The aircraft were test flown, dismantled, cocooned for protection from sea salt, and loaded on a cargo ships for Liverpool, England. The British Boulton Paul gun turret was installed upon arrival in United Kingdom. On 3 September 1939, the day U.K. declared war on Germany, 78 Hudson patrol aircraft were in service with the RAF, protecting the waters around England. Canada had eight British designed RCAF Stranraer flying boats protecting both coastlines, one in the West and seven in the East.

In November 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt persuaded the U.S. congress to amend their neutrality laws, permitting a cash-and-carry trade in American war material including aircraft. By March 1940, British orders in the United States had grown to over 26,000 aircraft, including aircraft which were diverted to the RCAF. The dismantling, loading on ships, transport by sea, unpacking, and reassembling, was no longer acceptable. On 16 August 1940, a new transatlantic ferry route was established and RAF Ferry Command began operating from Gander, Newfoundland [later a major airfield was constructed at Dorval, Quebec, the future H.Q. of Ferry Command]. This was the same year, Walt Disney artists were creating for free military insignia for American based units and also supporting the war effort in Europe, as American was still neutral in WWII. This became a huge part of nose art history and can be found on many websites, and books, including my own. The image below was possibly taken in August 1940; civilian ferry pilot “Pappy” Ryan received his paper work at the Lockheed plant in Burbank, California.

The Disney studio was located next door to Lockheed, and a Disney artist has drawn in chalk a war effort cartoon message for Germany. It is very obvious this was a posed promotional image from Lockheed Corporation in Burbank. Donald Duck holds a bomb as he points to Berlin – “We the Men of Gander, – Wish our hero Donald well, – When he catches up with ‘Adolph’, – The Fuhrer will get ‘Hell’.

Gander, Newfoundland, became a main fuel stop for all ferry pilots, under control of the United Kingdom, who would grant the United States a ninety-nine-year lease for air bases, in exchange for old WWI U. S. Navy destroyer ships. [Became law on 11 June 1941] Permission for the RCAF to patrol and establish bases on Newfoundland, was reached by U.K., Canada, and Newfoundland, on 17 June 1940, and the RCAF officially arrived on 28 August, the same month ferry command began operations.

The early ferrying of Lockheed Hudson aircraft from California, to Gander, Newfoundland, and then United Kingdom, opened up the flood gates for Disney RAF and RCAF insignia requests. Disney artist Hank Porter had already created two insignia for Lockheed Aircraft Corp. at Burbank, California.

The first insignia [left] was created for the American men and women who constructed the Lockheed bomber aircraft.

The second insignia features a California Golden Bear [wearing helmet] launching a Hudson bomber wearing RAF and RCAF roundel markings. Disney also created the famous USA “Lend-Lease” design of WWII.

From 26 August 1942 until late September 1945, Lend-Lease delivered 7,971 American aircraft to Fairbanks, Alaska, and turned them over to Russian pilots. In total 7,926 were flown away by Russian combat pilots, a duty which was regarded as a ‘rest from combat.’ The Soviets accepted 5,066 American lend-lease fighter aircraft, the most being Bell P-39 “Airacobra” [2,618] and P-63 “Kingcobra” [2,397].

In total United States delivered to Russia $9.5 billion in war material, tugboats, and aircraft. A few Soviet pilots thanked the United States by painting Disney Lend-Lease nose art. Today the big bad Russian Bear is acting just like Hitler did in WWII.

By the end of October 1939, RCAF Eastern Air Command had only two squadrons, Nos 5 and 8 [BR] equipped for the vital Halifax maritime reconnaissance role, in protecting the convoys for England. Just like the British, Canada was now forced to purchase the modern American Hudson patrol aircraft.

No. 11 [BR] Squadron had been quickly formed at RCAF Rockcliffe, Ottawa, [3 October 1939] and a month later equipped with ten new American Hudson aircraft [delivered to Ottawa by American Lockheed Corp. pilots] then rushed to Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. Due to the United States Neutrality Act at that date, the delivery of these American constructed Hudson aircraft by American civilian pilots to Uplands in Ottawa, was not really legal. [This would change in November 1940]. While this was officially recorded in the Daily Diary, it was kept secret from the press and the public of the world. The ten Hudson aircraft in RCAF markings were flown to RCAF Station Uplands in the early morning darkness. This new No. 11 [B.R.] Squadron was officially formed at RCAF Rockcliffe, but they trained at Uplands, or that is what the Diary states. By the time the sun came up, [3 Nov. 39] the ten were on their way to RCAF Station Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, flown by RCAF pilots. All’s legal in love and war, and Canada needed modern patrol aircraft to help the obsolete Stranraer flying boats at Dartmouth, N. S.

The Daily Diary for 3 November 1939, records all the details and the serial number of each Hudson aircraft.

Lockheed Hudson # 764 at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, in her new markings of No. 11 [B.R.] Squadron.

The Hudson became the first RCAF modern maritime-patrol aircraft to arrive on the east coast and at last provided the needed support for the Stranraer flying boats. The Hudson could fly 100 knots [115 m.p.h.] faster than the Stranraer and had a patrol range of 100 more miles, remaining in the air eight hours, [with 400 lb. bomb load] compared to the Stranraer six hours, [with 1,000 lb. bomb load]. The Hudson could remain in the air, four and one-half hours with 1,000 lb. bomb load, at speed of 213 mph. The Hudson also provided full protection for the aircrew and gunners unlike the open positions in the Stranraer. [seen below]

No. 11 [B.R.] squadron flew their first convoy [H.X.#11] anti-submarine patrol from Halifax on 4 December 1939, flying twenty miles ahead of the 40 ships. The instructions for the convoy patrol of No. 11 [B.R.] squadron are attached, the first RCAF Hudson patrol in WWII.

The next convoy H.X. #12 sailed on 12 December 1939, and the ship total [35] is growing in number, which included more work for No. 5 and No. 11 [B.R.] Squadrons. The responsibilities of Eastern Air Command continue to grow at a rate faster than its capabilities and they do not have any long-range aircraft. It is interesting to see the contents of each ship in the H.X. 12 convoy and where each ship will dock. In the total of 35 ships, eleven are carrying oil or gas, 1- Fuel oil, 1 – Gas and Oil, 1 – Petroleum, and 8 – Crude Oil. Seven carry Canadian wheat and two General Canadian grain and two carry Canadian Flour. The convoy will sail in 9 columns, with four ships in each column, other than column 4 which has three.

This secret order was used for briefing of No. 5 and No. 11 Squadron pilots, but no copies were allowed to be taken aboard the Stranraer flying boats or the Hudson Mk. I aircraft.

No. 5 [B.R.] Squadron [above] faced another problem which rarely appears in RCAF history books. When Canada declared war on Germany, the government specifically forbid the military to discuss or plan any defence measures with Newfoundland, a self-governing colony of Great Britain. Ottawa did not wish to assume any unofficial responsibility for the protection or security on the island. The Stranraer aircraft of No. 5 Squadron were not allowed to fly patrols over Newfoundland, unless they first obtained permission from Great Britain. By 13 March 1940, the Canadian Cabinet had persuaded the British and Newfoundland government that Canadian Army coast guns and Eastern Air Command aircraft of the RCAF should be stationed on the rock. Then in June 1940, France and the Low Countries fell to Germany and it was feared Germany might seize the airport at Gander and take control of the island’s communications. On 17 June 1940, the governments in Ottawa and St. John’s, Newfoundland, agreed for protection, and the Canadian Army, RCAF, and one seaplane station were soon established on the rock. In mid-August 1940, the Canadian minister of national defence for air, [C.G. Power] the new chief of the RCAF air staff, Air Vice-Marshal L.S. Breadner, and all of his senior Eastern Air Command officers met in St. John’s, Newfoundland. On 28 August this was renamed the Joint Service Committee Atlantic Coast, and Canada took control of a new agreement where all Newfoundland military forces now came under Canadian Command. This new revised Defence of Canada Plan strengthened the Atlantic region command and provided better security for all of Newfoundland. Newfoundland and Labrador soon became the major strategic location for the future Battle of the Atlantic against German U-boats. 1940 was a year of convoy patrol training, flying close escort patrols over a predictable route, which became too routine. It was also a period of erroneous reports of enemy submarine sightings and bombing these same targets, which were most likely whales.

No confirmed intelligence reports of any U-boat within extreme aircraft range of Newfoundland were made until 20 May 1941, yet a submarine [likely a whale] was seen and bombed on 5 June 1940. On 2 June 1940, the Canadian Government was informed by intelligence reports that Italy was preparing to declare war on France and United Kingdom. The RCAF was ordered to follow an Italian freighter “Capo Lena” in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, which was located by Stranraer #916 on 2 June 40.

On 10 June 40, Italy declared war on France and U.K. and the Italian ship was found beached and burning in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Canada declared war on Italy, [officially] on 11 June 1940. This became the only contact with an enemy ship for any RCAF Canadian Stranraer flying boats.

15 June 1940, became a date for many changes in new patrol areas, operational functions, and the combined use of new and old aircraft. Twenty new American Douglas B-18 [Digby] arrive in the RCAF and a new RCAF base in Newfoundland is established.

The most famous of all RCAF anti-submarine squadrons, No. 10 [B.R.] “Dumbo” Squadron was assigned to Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, on 15 June 1940, however her beginnings were the humblest of all. Originally No. 3 [B] Squadron, she was reformed as No. 10 [B] Squadron on 5 September 1939, becoming a Bomber Reconnaissance squadron on 31 October 1939. Assigned to Halifax, Nova Scotia, under Eastern Air Command, Home War Establishment, the unit aircraft strength called for fifteen twin engine Bomber Reconnaissance bombers, but the Canadian government and RCAF did not have any. They were now assigned thirteen old single engine 1927 fighter/bomber aircraft called Westland Wapiti Mk. IIA, which were obsolete.

The original orders for No. 10 [B.R.] on 30 September 1939, follow.

Wapiti Mk. IIA #542 in the squadron maintenance shack.

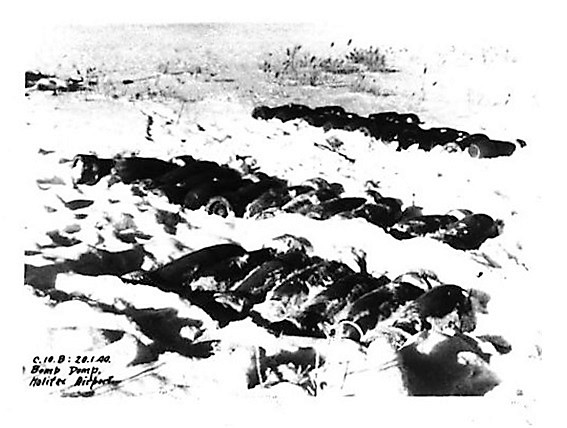

On 14 January 1940, No. 10 [B.R.] Squadron only aircraft maintenance shack burnt down.

The Halifax bomb bump was just a snow covered field, and the obsolete aircraft continued to suffer many problems. A more modern American replacement twin-engine bomber was soon on the way.

In February 1940, the Canadian government purchased twenty B-18A [Bolo] twin engine bombers from the Douglas Aircraft Company at Santa Monica California for $60,000 each. The problem was how to get them to Canada, as the American Neutrality law would not be amended until early November 1940. The first two ferry pilots to deliver the American Hudson bombers to England, Australian Capt. D.C.T. Bennett and American Capt. R. H. Page, established a route which did not break the American Neutrality Act. American pilots flew the Hudson bombers to the border at Pembina, North Dakota, and parked them a few feet from Canada. Pembina, North Dakota, [population 700 in 1940] is located two miles south of the Canadian-US border at Emerson crossing, directly south of Winnipeg, Manitoba. If you go directly south on interstate 29, you will arrive at Fargo, North Dakota. [Great movie] A tow line was next thrown across the border, where a Canadian farmer with a team of horses then hauled the aircraft into Canada, and the ferry crews flew them to Winnipeg, Manitoba, Montreal, Quebec, Gander, Newfoundland, and United Kingdom. These first ferry pilots were civilians, mostly American pilots who made $600 [US] for every aircraft delivered to United Kingdom. Many of these recruits were pilot adventurers, who had been thrown out of every American airline they worked for. They drank too much, chased too many women, had fist fights, but also possessed the courage to fly the vital bombers to wartime England. The RCAF just followed this civilian established ferry route and the twenty Douglas B-18 bombers were flown to Pembina, North Dakota. I’m sure the Canadian Manitoba farmer received a good cut for every aircraft he pulled into Canada.

This image appeared in Canadian MacLean’s magazine and captures an RCAF pilot [left] standing on the Canadian side of the Manitoba-US border as a farmer pulls a new Douglas B-18 bomber into Canada. This was taken around late March 1940, [snow on ground] as the first two Digby B-18 bombers were delivered to No. 10 [B.R.] Squadron at Halifax, Nova Scotia on 9 April 1940. S/L Carscallen and F/O Richardson flew to Moncton, New Brunswick, picking up the first two bombers, and twelve more followed. Serials were – #739 [P], #740 [R], #744, #745 [W], #747 [X], #748 [V], #749, #751 [Y], #752, #753, #754, #755 [J], #756 [M], and #757 [K]. These new Douglas bombers were a most welcome addition to No. 10 BR Squadron and served Eastern Air Command, with improved American horsepower and were even partly delivered by good old Canadian horsepower. In 1918, the British Air Ministry formed an agreement with the aircraft manufacturer where British aircraft were assigned an official pattern of given names.

British Heavy bombers and Transport aircraft were given names of British cities or towns, – Short “Stirling” – Avro “Lancaster” – Avro “York” – Vickers “Valetta.” The RCAF followed this pattern, and the new American Douglas B-18 twin-engine bomber was given the name “Digby” for the south-west coastal town of Digby, Nova Scotia, with a 1940 population of 1,600.

On 15 June 1940, No. 10 [BR] Squadron was transferred from Halifax to Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, [shown above – PB-V, #748, PB-X, #747, PB-K, #757]. The following day, 16 June 40, “A” flight with five Digby bombers are transferred to Gander Airport, where they arrive on 17 June 1940 at 10:50 Hrs.

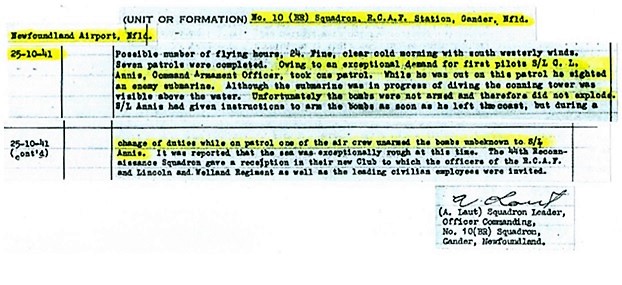

This was the beginning of the most famous RCAF anti-submarine squadron formed in WWII, and they would establish a record with 22 attacks on German U-boats, sinking three. The first squadron operation was flown on 17 June 1940, [Gander, Newfoundland] when Digby #744, pilot S/L Carscallen flew an anti-submarine patrol. The first patrol operation flown at Dartmouth was on 3 July 1940, when Digby #757, pilot F/O A. Laut flew an entrance patrol over Bedford Basin at Halifax harbour. The first German U-boat sighted [Eastern Air Command] was by No. 10 BR Squadron on 25 October 1941, and attacked by Digby #740, which dropped two 600 pound bombs, but failed to explode as they were not armed. The squadron had been equipped with Douglas Digby aircraft for six months, but still lacked pilots and properly trained aircrew.

This is Digby #740, [PB-R] which made the first German U-boat sighting in Eastern Air Command on 25 October 1941. Due to a shortage of qualified RCAF pilots, the Armament Officer was flying this patrol, and a mix-up in commands and lack of proper training, the bombs were not armed, and could not explode. The German U-boat got away, and the battles of the North Atlantic were just beginning.

The squadron would wait one full year, before they recorded their first U-boat kill. On 30 October 1942, F.L D.F. Raymes and crew [Digby 747 “X”] were returning to Gander base after completing a patrol. They sighted a German U-boat on the surface and attacked, position 47-47 North – 49-50 West. Four 250-pound depth charges were dropped and U-520 remains on the bottom today. This was the squadron’s seventh U-boat attack and they were still flying ten American B-18 Douglas Digby bombers. The squadron has now won the unofficial title of “North Atlantic Squadron.”

For their ‘unofficial” squadron insignia they turned to Walt Disney artists and the hero “Dumbo.” This 1941 film was only sixty-four minutes long, but became the most direct, appealing, and effective movie Walt ever produced. It cost a small fraction of the budgets for “Snow White”, “Fantasia” and “Pinocchio” but doubled its profit at the box-office, $1.6 million. [that’s 25 million today] The film rough animation draft was completed in May 1941, and this image was used by Hank Porter possibly a few months later. A live action feature of Dumbo is now in production, to be released March 2019.

The American 6th Recon. Group also used a Disney Dumbo, C.O. was the President’s son Elliott.

Halifax patrol area was now covered by four RCAF Squadrons, flying Stranraer, Digby, Hudson, and Lysander aircraft. Now the reader can compare the July 1940 performance data on each aircraft and decide what was best.

The beginning of 1941, was another year for major changes in the growing U-boat war, and Eastern Air Command would suddenly have to adapt to new weapons, tactics, and sophisticated technology to attack German U-boats, combined with training in new American Catalina long-range patrol aircraft, being constructed in Vancouver, B.C., from parts manufactured by Consolidate in California, USA. No. 116 [Auxiliary] Squadron was disbanded at Halifax, Nova Scotia, on 2 November 1939, and re-formed as a Bomber Reconnaissance Squadron on 28 June 1941. In early July, personnel were being transferred from No. 5 [B.R.] Squadron to form a division of trained airmen for 116 [B.R.] Squadron, flying the new American Consolidated Catalina [RCAF Mk. I and Mk. I B] long-range submarine patrol flying boats, parts manufactured in San Diego, California, U. S.A. Code ZD, “A” – Z2134, “B” – Z2139, “C” – Z2137, “D” – Z2138, “F” – FP296, “G” – FP294, “H” – W8431, “J” – W8432, and “M” – DP202.

Canadian built, Consolidated manufactured, Catalina Mk. I serial Z2138, ZD-O, No. 116 [B.R.] Squadron, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, July 1941.

No. 5 [B.R.] Squadron continued to fly and receive new Canadian built Supermarine Stranraer flying boats, which were now assigned to “Harbour Entrance Patrol”, “Inner Air Search”, or “Outer Air Search” at Halifax, Nova Scotia. The fourteenth constructed Stranraer #920 [survives today in England] was completed at the Canadian Vickers Plant in Montreal, [CV209] on 29 November 1940, and the RCAF assigned her to No. 5 [B.R.] Squadron, at Dartmouth, N. S.

The assigned ferry crew departed Dartmouth, N. S. by train on 29 November 1940, to return the new Stranraer #920 to their home base. For reasons not recorded in the Daily Dairy, the Stranraer was not ferried, but disassembled and placed on a railway car for shipment to Dartmouth.

The original and beautiful preserved Canadian built, RCAF flown, and then forgotten, Stranraer #920 was saved by the wonderful British RAF Museum, Hendon, London, United Kingdom, in 1970. It was restored in 1972, and correctly painted in the colors of No. 5 [B.R.] Squadron, RCAF Station Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. You can find much more on many websites and it makes for most enjoyable reading, but very brief in preserving her RCAF WW II past at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, or later at Bella Bella. B.C.

We in Canada have a difficult time in saving or preserving our WWII aviation past, and when we do, we paint if wrong, twist half the history, and then wonder why a new generation of Canadians have no idea what a Stranraer flying boat looks like or where it flew. In my first part of Vickers Supermarine Stranraer history, I have attempted to tell the truth as it appears in the Daily Diary, and make it easy to digest and understand. I will now report important sections of the WWII operational history of flying boat #920, in two parts. Stranraer #920 first arrives at Dartmouth on a railway flatcar, [22 December 1940] was assembled, air tested, and approved at 14:35 Hrs. 21 January 1941.

The first official duty for RCAF Stranraer #920 was Public Relations, when she flew the National Film Board of Canada, who were making a documentary on the convoy lifeline to the United Kingdom.

This is what Stranraer #920 saw in Bedford Basin, Halifax harbour, 1941.

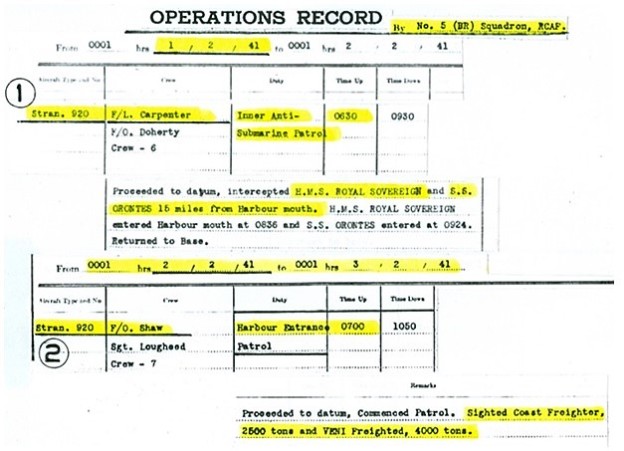

The first official RCAF anti-submarine patrol flown by Stranraer #920 is on 1 February 1941, Bedford Basin, Halifax harbour, F/L Carpenter.

In the last week of October 1939, Eastern Air Command placed the slower No. 5 [B.R.] Stranraer flying boats in patrols to protect the Entrance, Inner, and Outer sections of Halifax harbour for protection of the convoys as they were forming up, and preparing to leave for United Kingdom.

From 1 February until 15 July 1941, Stranraer #920 completed a total of 43 of these three Halifax patrols. I will only list the records for her first month of operations, February 1941. This will give readers/historians some idea of the work involved in forming, sailing, and protecting one [H.X.] Halifax to United Kingdom convoy in February 1941. Stranraer #920 few ten patrols in February 1941, two were Inner harbour, one was Outer harbour, and seven were Harbour entrance. Dates: 1 Feb 41 – Inner, 2 Feb. 41 – Entrance, 14 Feb. 41 – Entrance, 16 Feb. 41 – Entrance, 17 Feb. 41. – Inner, 18 Feb. 41 – Entrance, 20 Feb. 41. – Entrance, 21 Feb. 41 – Entrance, 24 Feb. 41 – Entrance, 28 Feb. 41 – Outer.

During this time period, Stranraer #920 provided [Scare-Crow] air cover for seven convoys, totalling 177 ships that departed Halifax for United Kingdom.

3 Feb. 41 Convoy H.X.107 20 ships.

9 Feb. 41 Convoy H.X.108 28 ships.

12 Feb. 41 Convoy H.X.109 23 ships.

17 Feb. 41 Convoy S.C.23 40 ships. S.C stands for “Slow Convoy.”

19 Feb. 41 Convoy H.X.110 26 ships.

22 Feb. 41 Convoy H.X.111 15 ships

28 Feb. 41 Convoy H.X.112 25 ships.

Her last [#43] Halifax convoy duty on 15 July 1941, was protecting convoy H.X.139, which contained 47 ships headed for United Kingdom. This RCAF flying boat #920 has provided air cover for 32 convoys, over 800 ships, leaving Halifax harbour with a lifeline of material for the British people, and her job is not yet completed, she is just moving north to No. 5 [B.R.] Detachment North Sydney, [Kelly Beach] Nova Scotia.

These are the twelve new Stranraer patrol routes [S-1 to S-12] which were created on 25 May 1941, and first flown by Stranraer #909, #919, and #923. The three Gaspé [G-1 to 3] patrols meet at Cape Breton Island. On 16 July 1941, Stranraer #920 was urgently needed and transferred to No. 5 [B.R.] Detachment at North Sydney, [Kelly Beach] Nova Scotia, where she joins the other flying boats.

The Stranraer patrol range and patrol number is recorded on the map and marked in yellow. Stranraer #920 makes her first flight [test-practice] on 18 July 1941, with a crew of eleven, completing ten more anti-submarine patrols for the month, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 28, 29, 30, and 31 July 1941.

In August 41, Stranraer #920 completes ten more patrols: 3, [lost an engine], 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 29, and 30.

On 3 September 1941, the squadron is officially presented with their unit Badge: A gannet in flight and Motto – “Volando vincimus [By Flying We Conquer]. The squadron’s combat patrols coincide with the area the gannet is found, where it tracks and attacks fish, the same functions as the Bomber reconnaissance squadron locates and attacks enemy shipping.

Authority: King George VI, signed June 1941.

The Gannet is a large white seabird with a yellowish head, black tipped wings, and long bills. The most important Gannet breeding site in Canada is Bonaventure Island, Quebec. At one time Canada had an aircraft carrier with that name.

In September 1941, Stranraer #920 completes nine patrols, 2, 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14 and 17. The flying boat then receives a ten-hour inspection, and is test flown on 18 September 1941. On 21 September the aircraft is ferried back to her home base at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, for the last time.

Stranraer #920 arrives in Ottawa, 06:35 Hrs., 23 September 1941. She is on her way to patrol for Japanese submarines on the West Coat of Canada, at RCAF Station Bella Bella, B.C.

The successor to the old Stranraer became the Consolidated PBY Catalina, manufactured in Canada by Boeing Canada, Vancouver, from parts manufactured in the Consolidate plant in California. The Canadian Vickers plant in Montreal, and later a new plant at Carterville, Quebec, manufactured and constructed the new Canadian Catalina, and now the RCAF were ask to give it a new Canadian name.

The Harbour of Cape Canso has been an important fishery base since 1518. The small community of Canso was established in 1605, located today on the north-eastern tip on mainland Nova Scotia, Canada. On 10 July 1939, the RCAF began preparing for the defence of the east coat and the above map records the name Cape Canso as an important reference point for both ships and aircraft. Cape Canso became the division between the patrol area for Halifax, Nova Scotia, and the northern patrol area of Sydney and North Sydney, Nova Scotia. From the declaration of war on 10 September 1939, until 18 September 1941, Canso village was used by Stranraer aircraft, including #920, as a vital point of reference for hundreds of patrols protecting the ship convoys leaving Halifax harbour.

The 1918, naming of aircraft by the British Air Ministry assigned all Flying Boats with the name of a coastal port or community in United Kingdom, Short Sunderland, Supermarine Stranraer, [southwest shore of Loch Ryan, Scotland]. The RCAF followed this British official pattern, and the new Canadian manufactured Catalina flying boats were named in honor of the village of Canso, Nova Scotia, 25 July 1941.

Both the American Douglas B-18 Bomber, “DIGBY” and the Catalina PBY Flying Boat “CANSO” were named in honor of two Nova Scotia fishing communities, where they flew patrols and protected the East Coast during WWII.

No. 5 Squadron sighted 25 German U-boats, made 17 bombing attacks and Canso A, serial 9747 sank one U-boat [U-630] on 4 May 1943. They lost three aircraft and eleven aircrew members were killed in action. The squadron was disbanded at Gaspé, Quebec. on 15 June 1945.